Roaring Fork Valley’s mushroom hunting season looking dry

Beau Toepfer/The Aspen Times

Within the 2.3 million acres of the White River National Forest are a number of fungi species people are about to start searching for.

This mushroom hunting season, however, is looking dry. There hasn’t been a lot of rain, and the rain that has fallen has been inconsistent. This has left the soil arid, prevented the growth of fungi, and slowed down decomposition. According to Andrew Wilson, the curator of mycology at Denver Botanical Gardens, fungi grow better and quicker, like any plant, after consistent heavy rain. Fungi need saturated material to grow out of, whether that be the soil or the detritus it decomposes.

“If you’re walking along the forest floor and it’s all crunchy and crackling, you’re not going to find very much,” said Ed Lubow, who’s been a mushroom hunter in Colorado and the U.S. for 50 years.

When you see a mushroom, you see the fruit of a complicated underground system. If you’ve ever flipped a log and seen white tendrils that look like little cobwebs, that’s mycelium, or the “business end” of the fungi, according to Wilson. Those tendrils aren’t the roots of the fruit, but instead they function more similarly to the leaves of a tree, gathering nutrients and creating energy.

“Fungi are the best decomposers on earth,” he said.

When the mycelium matures, they sprout up the fruit, which can distribute spores to reproduce. According to him, humans have two mating types, male and female, which have to reproduce to create offspring. Fungi, like schizophyllum commune, for example, have 23,328 mating types, and only two have to come in contact to create an offspring.

But when there’s no rain or moisture, those fruits never sprout, and no new offspring are created. During arid periods, mycelium will slow down their decomposition rate, and much of it will go dormant.

“Right now, what we need is probably two weeks of good regular rainstorms, and then we’ll probably enter into peak mushroom season,” Wilson said. “As long as the mountains can continue to see regular monsoons come through later in the seasons and those monsoons have plenty of moisture to deposit onto the mountaintops, mushrooms will keep coming back.”

But climate change has affected the rain patterns in Colorado, he added, and the Colorado Water Conservation Board confirmed droughts are expected to get worse and more frequent, leading to less consistent mushroom hunting seasons, and also worse wildfires.

It’s not just about mushroom hunting, though. Fungi do more for forests than feeding humans. According to Wilson, they are the foundational element of a process called “coldfire.” Fungi, specifically wood decomposing fungi, can break down forest detritus without scarring the soil, releasing carbon, or causing wildfires.

“Learning how to take these wood decaying fungi to break down woody debris, what you’re doing is you’re replacing fire and a lot of these ecosystems because what forest managers are trying to do is thin out spruce (and other trees and detritus) because we don’t necessarily want the fires to be doing it,” he said.

Wildfires can scar and “sterilize” soil, and it could take up to a decade for plants to be able to regrow, he said. Fungi are also a substitute for pile burns, where forest managers pile ladder fuel and ground fuel into piles to burn, which can sterilize those sections of soil.

Fungi also play an important ecological role in feeding animals, especially rodents and squirrels

According to Wilson, there are estimates that humans only know less than 5% of fungal diversity.

“I feel like it’s wide open,” Jess Loeffler, a CU Denver graduate student studying mycology, said. “There’s a lot of people doing a lot of really cool work … I feel like advances in technology have really opened up what’s possible (to learn).”

PHOTOS: Aspen Rotary’s Ducky Derby fundraiser returns to the Roaring Fork

The annual Ducky Derby race returned on Saturday to the Roaring Fork River.

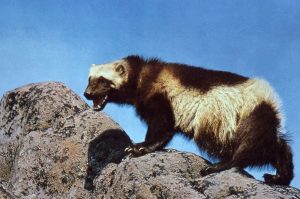

Aspen area included in ‘release zone’ for wolverine reintroduction

The Aspen area has been included in one of three general release zones for the reintroduction of wolverines into the state, according to preliminary information from Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s developing plan.