Pitkin County plans for ‘unprecedented’ federal food aid pause

County to issue temporary grocery gift cards, direct funds towards food pantry, to account for SNAP interruption

Gray Warr/The Aspen Times archives

As the federal government nears its first full month of shutdown — the second longest in American history — food aid funding has landed in the crosshairs.

Beginning Nov. 1, 335 people in 235 households across Pitkin County will be unable to receive benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, according to a press release, unless the federal government approves temporary funding. SNAP (formally known as the Food Stamp Program) funds food purchasing for low-income individuals, with roughly 41.7 million people nationally relying on the program per month, according to the United States Department of Agriculture’s 2024 average monthly statistics.

“This is unprecedented,” said Pitkin County Human Services Director Lindsay Maisch, who leads the department that distributes food-purchasing funds to county residents in need.

Maisch said she has never encountered a situation like this in her nearly four-year tenure as director of Human Services, nor had her predecessor, Nan Sundeen, who held the position for 30 years. The SNAP pause would be the first in the program’s history.

Pitkin County distributes approximately $66,000 per month in SNAP funding to county recipients, the press release states. If there is no federal shift by Nov. 1, the county will issue temporary grocery gift cards — as soon as Nov. 5 — to those enrolled in SNAP, with the amounts based on households’ typical monthly SNAP benefits.

According to the Colorado Department of Human Services, those eligible for SNAP benefits must have an income less than 200% of the federal poverty level. The SNAP income limit for a household of one is $2,610 per month — $31,320 per year. The income limit for a household of four is $5,360 per month — $64,320 per year.

To obtain a gift card from the county, SNAP members must go to the Schultz Health and Human Services building, 0405 Castle Creek Road in Aspen, between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., Monday through Thursday. The department can be reached at 970-920-5235.

Recipients must present identification and sign an agreement to only use the cards for “SNAP-eligible groceries,” the press release states. Maisch said the county is going to purchase $5,000 of grocery gift cards the first week of distribution — starting small to gauge the demand.

“We’re just going to take it a week at a time in small amounts,” she said, adding that the county could pivot to increase grocery funds if demand increases.

The county is also helping fund the local food pantry, Harvest for Hunger, which is asking for approximately $4,500 per month in additional funds to account for an increase in expected food demand, according to Harvest for Hunger Founder and Executive Director Gray Warr.

“We are basically going to double our weekly food order from Food Bank of the Rockies to meet that demand,” Warr said.

In addition to the 335 people using SNAP benefits in Pitkin County, he said Garfield County is host to about 4,000 SNAP members. He estimated that 15% of those members work in Pitkin County, so expected there to be 935 total SNAP members across both counties “who have the potential to visit our pantries.”

Pantries are located at Pitkin County’s Health and Human Service Building, 0405 Castle Creek Road in Aspen, at Snowmass Town Hall, 130 Kearns Road, and at 325 E. Cody Lane in Basalt, the headquarters of Response, an organization helping survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault. Warr noted that the Response pantry is only open to those already being helped by the organization.

Those wishing to support Harvest for Hunger can do so at harvestforhungerco.org/donate.

The funding for both the supplement to Harvest for Hunger and the grocery gift cards will come from Pitkin County’s $200,000 Emergency Assistance Fund, which is a subsection of the county’s General Fund, according to Deputy Pitkin County Manager Kara Silbernagel. She said the last time the county tapped into the emergency fund was during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

“It’s something we budget every year, hope to never have to use, but want to always have available for exactly these kinds of emergencies, (so) we can react and respond as necessary,” she said, “whether it’s government shutdown, wildfire, flood or … pandemic.”

If the federal shutdown continues through mid-November, Pitkin County said in the press release that it will “assess the need and supply of additional grocery cards for the following month.” Silbernagel anticipated the county could cover a SNAP shutdown through the end of December but noted that if the shutdown were to continue into January, the county might have to focus on “much broader impacts” related to the shutdown.

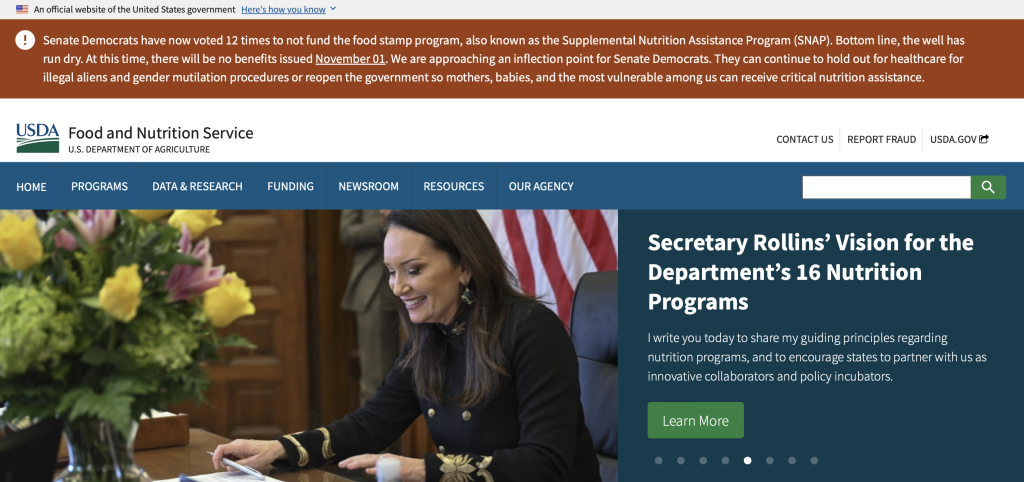

The USDA blamed Senate Democrats for the Nov. 1 pause in SNAP, writing on their website that the “well has run dry” and that Senate Democrats “can continue to hold out for healthcare for illegal aliens and gender mutilation procedures or reopen the government so mothers, babies, and the most vulnerable among us can receive critical nutrition assistance.”

Colorado joined 24 other states and the District of Columbia in a lawsuit against the Trump Administration on Tuesday after the administration announced last week that SNAP would be suspended, refusing to rely on roughly $5 billion in SNAP contingency funds that were to be used in the event of a funding lapse.

The USDA reportedly deleted a notice on Oct. 23 that said the contingency funds could be used for SNAP benefits before releasing the memo last week saying “contingency funds are not legally available to cover regular benefits.”

The federal shutdown comes after the U.S. Senate could not agree on federal expenditures by the Oct. 1 deadline — the start of the federal government’s fiscal year. Senate Democrats refused to agree to funding cuts to the Affordable Care Act, an act that subsidizes health insurance premiums through tax credits and is set to expire at the end of the year unless approved.

The act covers those who are not provided health insurance through a job, as well as those who don’t have an income low enough to qualify for Medicaid — a public program that helps provide health insurance to those making less than 138% of the federal poverty level, or $21,597 for single individuals, though eligibility varies by state. The act also covers those who don’t qualify for Medicare, a public program making health insurance affordable for individuals age 65 or over.

This year, 24 million Americans were enrolled in the Affordable Care Act, about 7% of the U.S. population. KFF, an independent source on health policy, estimated those enrolled in the Affordable Care Act would see a 114% average increase in their health insurance premiums, more than doubling what they currently pay on health insurance per month.

Should the Affordable Care Act tax credits expire, as many as four million individuals could become uninsured, according to an estimate from the Congressional Budget Office.

Skyler Stark-Ragsdale can be reached at 970-429-9152 or email him at sstark-ragsdale@aspentimes.com.