Part 1: Mental health pros work to stay in touch and combat stigma

Aspen Hope Center/Courtesy image

Editor’s Note: This story is part one of a three-part series on mental health in the Roaring Fork Valley.

In the summer of 2019, when Andrew Parrott was in crisis with bipolar disorder, a Pitkin County sheriff’s deputy reached out.

“I was going through a pretty dark period,” Parrott said. “And Grant Jahnke … came over and he said to me, ‘You know, if you ever just need someone to sit on the sofa and have a beer and listen, this is Aspen. That’s what we’re here for.'”

Parrott was not sure he could make sound decisions for himself, and he placed his trust in Jahnke to step in at the level of a close friend or family member — a rarity he called unique to Aspen.

His confidence in Jahnke and the Pitkin Area Co-Responder Team (PACT) to make decisions in his best interest marks a departure from the traditional disciplinary relationship between the police and the people they serve.

To someone visiting Aspen, the ski town town nestled in the Rocky Mountains may appear something like paradise. But if so, there is certainly trouble in paradise.

According to Mental Health America, nearly a quarter of Colorado residents have a diagnosed mental illness, defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration as “having a diagnosable mental, behavioral or emotional disorder other than a developmental or substance use disorder.”

In the past few years, the Roaring Fork Valley has changed through a mission to fill gaps in resources for people struggling with mental health. What was once a relatively barren space with minimal resources is now a growing ecosystem of organizations and agencies. But the question remains — are the resources sufficient for the mental health struggles of the community?

Four years later, in March, Parrott again found himself in the throes of a mental health crisis. Remembering what Jahnke had said to him four years prior, he called him and asked for support. Jahnke came over with PACT clinician Kat Buesch to sit down with Parrott and create a support plan.

“They sat down and they talked with me, and they have both continued that relationship for several months — through a hospitalization, through a behavioral health program I’ve done, through many, many ups and downs, through some seriously dark days,” Parrott said. “The PACT program has unequivocally not only saved my life but helped give me the will to continue living.”

According to Pitkin County Public Health Planning and Programs Manager Jenny Lyons and Mental Health Program Administrator Katie Hundertmark, PACT works with clients to help connect them with mental health resources.

Generally, when PACT is called to respond to a situation, a clinician from Mind Springs Health responds with a law enforcement officer. After the call, the clinician works with a peer specialist and case manager from PACT to develop a follow-up plan depending on the client’s needs and desired level of support.

“I think PACT is particularly good in our community as a bridge for people who may not want to immediately engage in other mental health treatment,” Lyons said. “We can show up and kind of meet them where they are.”

She said that not all of PACT’s clients may be enthusiastic about reaching out to outside resources. PACT members accept that reality and continue to offer support.

“We keep showing up for folks and trying to meet them where they are and offering them what we can so that hopefully, we are there when they might change and decide that they are ready for additional services,” she said.

Every few days, Parrott receives a call from Jahnke, Buesch or someone else from the PACT program to check in on him.

“It keeps me accountable,” he said. “Because on the days that maybe I don’t feel like I have the strength to do it for myself, I remember how much the people who love me have invested in helping me and in keeping me here. And I do everything I can to show up for them.”

In contrast to for-profit mental health care institutions, PACT, as well as the Aspen Hope Center, has no financial incentives for providing mental health support, cultivating a system of care centered on the client’s well being rather than profit.

“On a fundamental level, the most important thing was that it was clear that they were there for me,” said a person who was raised in the Roaring Fork Valley and has worked with the Hope Center for more than six years but wished to remain anonymous out of concern about being stigmatized. “There’s not any ulterior motive. … They really want to be there for you long term.”

The Hope Center focuses on connecting people experiencing mental health crises with the appropriate resources, providing crisis intervention, suicide prevention, mobile crisis response, therapy, school-based programs, referrals, and check-ins. The Hope Center also operates a 24/7 crisis hotline.

According to the person from the Roaring Fork Valley who has been receiving support from the Hope Center for years, the ability to speak with someone over the phone at any hour can be crucial for someone experiencing serious mental health issues.

“It was important for me at that time when I was actively suicidal to have around-the-clock support,” they said.

Parrott said connecting with a continuous support system he can talk to about his mental health challenges and who accepts him as he is can be invaluable, serving as a reminder of his personal worth.

“It gives me hope that I’m salvageable and worth something and bigger than this disease that can at times just totally take control of me, even on meds, even with all the best help, even with people who love me, even with a great job and income,” Parrott said. “Disease doesn’t care about stuff like that. It’ll take it all away in an instant, and you need an extraordinary amount of grace and love from the people in your life to keep waking up every morning.”

Stigma surrounding mental health

Once accessed, the support one receives can be invaluable. However, the stigma that surrounds reaching out for help can often pose a barrier to accessing that care.

For Parrott, sharing his story comes with an inherent risk to his career, he said, which revolves around building relationships and connecting with people in the tech industry. Even for someone like him who has had a successful and accomplished life by conventional standards — leading executive talent acquisition at major companies, attending West Point — speaking publicly about his struggles with mental health puts him in a vulnerable position.

“Every time I talk about it publicly, I risk my career, I risk the livelihood that allows me to be fortunate enough to live in a place like Aspen, and that is incredibly scary to me,” he said. “It’s difficult, it’s embarrassing, it’s stigmatized, it’s infinitely complex.”

According to the 2023 Pitkin County Community Mental Health Assessment, the most common deterrents to discussing mental health for English and Spanish respondents were concerns they would be judged by others, and not feeling comfortable discussing the subject.

Parrott said the close-knit nature of the Roaring Fork community creates a space in which people genuinely care about each other, easing the stigma around discussing mental health, as well as the process of repairing relationships.

“When people care, they care, and they will bend over backwards for you,” he said. “I’ve apologized to everyone from dentists to accountants, and they’ll accept your apology, they’ll root for you, they’ll want to see you get better. They’ll be there to help.”

Even in a supportive environment, it can be incredibly challenging to confront the personal damage caused to relationships by mental illness, he said.

“It takes away the relationships and the lifeline,” Parrott said of the “otherworldly” force of his bipolar disorder. “It takes the humanity out of me and breaks all of those bonds that I have worked so hard to build, just because they’re people I love, much less the fact that they’re people who helped keep me alive.”

After emerging from the depths of a mental health crisis, Parrott has to confront bruised and perhaps broken relationships.

“I get back and I begin the work of asking myself, what did my bipolar do to the people I love the most despite my best efforts? What can I do to make those relationships right? Will those relationships ever be right? Is there any hope?” he said. “When mental illness rears its head and destroys connections I’ve worked a lifetime to build with people who mean the world to me, it is incredibly difficult to come to grips with that. It’s difficult to dust yourself off and apologize and restart for the nth time.”

Although there has been a trend toward more discussion in the public sphere surrounding mental health, Parrott said he is skeptical that the reality of the societal attitude toward mental health matches the rhetoric.

“It’s one thing to talk about it; it’s another thing to hire a person who has learned to manage or who is struggling to manage mental health issues,” he said.

To move beyond conversation into the realm of tangible action, Parrott suggested that empathy is the most powerful tool.

“Until people realize how connected we are, how one or at most two degrees of separation they are from someone who struggles in a major way with these things, there will not be the requisite empathy for someone to feel compelled to take that chance, to offer that aid,” he said.

A supportive community — including psychotherapy, hospitalizations, check-ins from PACT and the Hope Center, and supportive friends — has undoubtedly been instrumental in Parrott’s recovery journey. He said they have increased his resiliency and helped remind him of who he is beyond his mental illness. Even with that support, he emphasized that the strength to overcome mental illness must come from within the individual.

“Every person has to find within themself that someone or something to keep living for,” Parrott said. “Without that, the best help in the world will not be enough. … External forces can help with that journey, can make that journey easier, but ultimately that has to come from within. … In 39 years of experience, it’s got to come from the soul center.”

Aspen Fire Protection District pushes two ballot initiatives to improve funding

The Aspen Fire Protection District is presenting two funding proposals for the Nov. 25 ballot: a mill levy extension of 0.24 mills and a new sales tax of 0.5%.

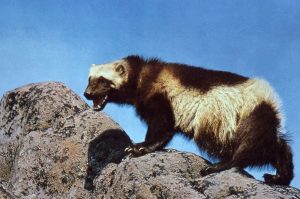

Aspen area included in ‘release zone’ for wolverine reintroduction

The Aspen area has been included in one of three general release zones for the reintroduction of wolverines into the state, according to preliminary information from Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s developing plan.