Italians opening new portal to Yule quarry in Marble

ALL |

MARBLE, Colo. – Work is under way to drive a new portal into the seam of unique white marble at Colorado Stone Quarries, Inc., in what the quarry’s administrative manager, Kimberly Perrin, said is an important new development in the business.”This is historic,” she said. “It’s the first new portal into the seam in more than 100 years. This will bring us 65 to 100 years of production.””It’s critical that we get as far into the mountain as possible before winter comes, so we can work up here in the winter,” she added.She estimated that the new portal is presently less than a third of the depth required. A structure will be erected at the portal entrance to protect it from avalanches and keep out the coldest winter air.The quarry, located in the upper Crystal River Valley, south of Carbondale and outside the tiny town of Marble, is operated by a partnership of the RED Graniti company and Locati Luciani Enrico & C.s.a.s. of Carrara, Italy. It was reopened in 2011 after it had been closed by its previous owner, Polycor, in 2009, due to financial losses. “This is the future of the quarry,” said Enrico Locati Luciani, an Italian who has been associated with the quarry for two decades and bought it from Polycor for an undisclosed amount in October 2010.He was visiting the quarry last week with his son Francesco to check on the work at the new portal, among other duties.He also got to see the new Fantini cutting machine, recently purchased and installed at a cost of $700,000. It is at work on the new portal and already has produced usable blocks of marble.In heavily accented English, he added, “We know the material is, ah, very nice,” as he gazed up the hillside at the new portal.The Yule marble quarry, first opened by George Yule, has been in operation off and on since its commercial possibilities were first recognized by Yule in the 1870s.Blocks of Yule marble have been used in scores of famous buildings and monuments across the country. In addition, the quarry has produced slabs, columns, flooring and other pieces for interior decorative use in homes and commercial buildings around the world.A small amount is also sold to artists, including those attending the MARBLE/marble Symposium going on this month in Marble.”We love artists,” Perrin emphasized. “We will always sell to artists.” But marble for sculpture accounts for less than 1 percent of the quarry’s sales.

The two Italian firms operating the quarry are in the running to be the largest block and quarrying operation in the world, shipping marble first to Italy and then to customers worldwide, she said.The quarry employs about 20 people, most of whom commute to Marble from neighboring areas.The marble seam is about 300 feet wide, 300 feet deep and runs for three miles to the south, Perrin said.In the quarries early days, quarry workers mined marble through three portals cut into the exposed face at the top of the seam, cutting into the seam and working their way downward.Once blocks were sawed out of the seam face, they were raised by wooden cranes to the portal.For much of the quarry’s history, the multi-ton blocks were slid downhill on a system of wooden rails to a small railroad along Yule Creek, which would deliver the blocks to the mill site in Marble. In a later development, the company built a 3.5-mile tramway down a steep grade to the mill site.At the mill, blocks would be cut and prepared for shipment on the old Crystal River & San Juan Railroad, a spur line extended in 1907 from the Crystal River Railroad’s original terminus above Redstone.”Now, we put it in a truck and drive it down the road,” Perrin said with a smile. Trucks can be seen hauling marble blocks downvalley to Glenwood Springs and onto I-70.Perrin, 59, has worked at the quarry in different capacities, and under different ownerships, for a decade. For a time, she operated a cutting machine carving out blocks of marble from the seam.”I’m a quarry rat,” she said with a laugh, describing herself as just another of the eccentric cast of characters attracted to the mystique of the Yule quarry and life in Marble.”Colorado Yule marble is unique from any other marble,” Perrin said. “It’s special because of a very white background with a golden vein.”Magnesium makes the gold coloring, Perrin said, and small nuggets of pyrite, known as fool’s gold, also are found in the stone.Only about 30-35 percent of the stone quarried actually makes it into the sale inventory. Much is rejected due to faults and discoloration.”In the mining industry, that’s huge,” she said of the percentage of saleable rock. Some quarrying operations retain less than 10 percent of the material produced. For instance, she said, a black marble quarry in Canada sells only 3 percent of its quarried rock.Perrin said that Colorado Stone Quarries is producing about 50 blocks per month of saleable marble.With the new portal, she said, the company expects to double that rate of production.

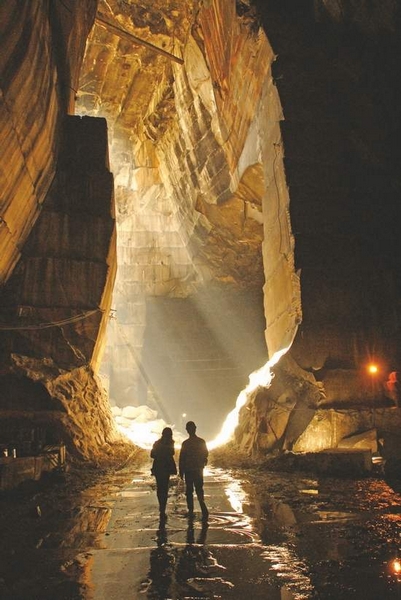

There are 18 people working in the quarry, some of whom live in Marble or elsewhere in the Crystal River Valley, while others live as far away as Montrose or Glenwood Springs.They enter the quarry through an access tunnel that was blasted through the rock in 1990, at the level of the quarry floor, giving people and machines access to the quarry space. The quarry portals themselves, however, are up close to ceiling level, near the top of the marble seam.Inside, at the level of the tunnel, the ceilings of the main quarry galleries are hundreds of feet above, with walls slanting inward as they go up.On July 18, operator Luke Hamilton of Cedaredge used an electric gallery saw to cut the stone. It’s like a slow chainsaw that’s liberally lubricated with water. He cuts into the face of the marble seam, at ceiling level and about a dozen feet off the floor.When he is finished, his cuts will have created six large blocks of marble, connected to the seam only at the back of the block. The block will then be separated from the face using either a saw or a water bladder that, when pressurized, will force the block away from the main seam.The blocks, held apart by propping stones so they do not touch each other, are then individually pulled away from the face using a huge forklift, and moved further from the seam face by a monstrous loader.Perrin’s job is to grade the blocks for quality, and decide whether they should be discarded as scrap or kept for inventory. A huge, diesel-powered loader operates inside the quarry, moving blocks around and performing other tasks. Although the crew is cutting into snow white marble, the diesel exhaust has blackened much of the rock face inside the quarry.Once a block has been pulled away from the seam, a technician standing at a control panel uses a remotely operated wire saw to trim the block.The blocks then can be moved, using the large front-end loader, to an area for storage until they can be marketed and sold.

Water seeps down from the rock that rests atop the marble seam, sometimes in vast amounts that can freeze when temperatures plunge to 30 degrees below zero in the winter.”You’re fighting something all the time up here,” Perrin said, whether it’s the cold or the water.”If we didn’t pump it out, it would fill up like a bathtub. We pump out, like, 40,000 gallons a day,” she said. Some of it is pumped to reservoirs for use in the quarrying operation, but the rest is sent to settling ponds and, ultimately, into Yule Creek and the Crystal River.”Calcium carbonate, that’s what marble is, is the best stuff for the water,” she said. “It balances the pH [acidity], it’s not toxic. It’s why we have such good water in the Crystal.”For the future, according to Enrico Locati Luciani, “I have a lot of ideas for this quarry.”One idea, he said, is to create a finishing factory somewhere nearby, which will allow him to cut down on costs by eliminating the need to ship stone to finishing plants in Italy.It also would improve his access to the U.S. market, he said.”The prospect for the future is very good,” he declared, grinning as he surveyed the quarry.jcolson@postindependent.com