How wildfires are impacting Colorado’s wildlife

A historic wildfire season in Colorado has seen fish evacuations, hunting license changes and more as wildlife adapts to burning habitat

Incident Management Team for the Elk and Lee Fires/Courtesy Photo

With wildfires raging across Colorado amid extreme drought conditions, the state’s inhabitants — human and wildlife alike — are bracing for impacts. On Friday, Aug. 22, around 207,500 acres were burning across the state in 17 fires. The vast majority of this acreage is attributed to nine large fires on the Western Slope.

“Wildfires can have significant negative impacts to the landscape, wildlife, and homes,” said Brad Banuli, Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s northwest region senior terrestrial biologist.

In the last month, wildfires have prompted Parks and Wildlife to evacuate hundreds of native trout from the Stoner Mesa Fire in the San Juan Mountains, monitor a variety of wildlife species and habitats, and alter fall hunts for certain bear, elk, and deer populations in northwest Colorado as the Lee Fire outside of Meeker joins the state’s largest fires in history.

While the impact of fires on wildlife depends on the fire’s intensity, growth, speed and size, it can impact animal distribution, migration, and daily movement as animals seek water, food, and shelter, Banuli said.

Despite negative impacts, including the growing intensity and risk of wildfires in urban-wildland interfaces, wildfires are natural parts of many Colorado ecosystems.

“Wildfires can also help to reset and restore the landscape by resetting succession in vegetation communities from older, less productive communities to more diverse and vigorous vegetation communities that create diversity across a larger landscape and can benefit different wildlife species than those that use older, successional communities,” Banuli said.

For more information on species specific impacts: The U.S. Forest Service has an online fire effects information database, which provides research insights on the impacts of wildfire on different species and in different regions. It can be accessed at Research.FS.USDA.Gov/FEIS.

What happens to wildlife during wildfires?

“Most animals survive fire,” said Gavin Jones, a research ecologist with the U.S. Forest Service’s wildlife ecology program at the Rocky Mountain Research Station.

A 2022 study of mammalian and reptilian survival before and after fires in North America and Oceana reported that around 3% of animals are killed during fire.

Many species that live in historically fire-prone areas have evolved to survive the blazes.

“Animals have adapted warning systems and have to be able to recognize those dangers,” Jones said, adding that they’ll sense smoke and heat changes or hear crackling flames and embers.

“In a place where fire commonly burns or has commonly burned for a long time, you’re going to have animals that sort of are primed to sense and be able to respond quickly and appropriately to fires when they come along,” he added.

While it’s species-dependent, there are a few ways that animals survive fires.

“Probably the most common — especially for animals that can move quickly, like birds and larger animals — is they’ll run away,” he said. “Some animals will actually double back into places that have recently burned in order to avoid the oncoming firefront. That’s a strategy that a lot of wildland firefighters use: It’s safer to go back into the black.”

Additional strategies include species that will shelter in place, burrowing into the ground or climbing into trees, as well as those that will have a psychological response, going into a sort of short-term hibernation to avoid the trauma of a fire, he listed.

For those that flee during fire, “wildlife generally adapt and use the closest available habitat to their traditional home ranges, but they may have to move farther to find quality food, shelter and water,” Banuli said.

What happens to wildlife in a post-fire environment?

In most cases, once the fire is done burning, animal species return.

“Then, the question is, how do they survive in those post-fire environments? What’s the change to ecology of that environment?” Jones said. “Wildfire is a natural process in so many of the systems that we know and love. And it’s a regenerative process, so it sort of restarts the ecological trajectory in a system.”

The timeline in which species return often comes down to what their “specialty” is, he added. As in any ecosystem, in a post-fire environment, different species play different roles.

“There are certain species that will recolonize like a recently burned area right after a fire,” he said, adding that this includes many plant species as well as woodpeckers that rely on larvae and other bugs that turn up and live in dead, burned trees.

For most, fires trigger a period of exploratory behavior.

“From the animals’ perspective, this is now a new environment and the distribution of resources has also changed,” he said. “They’re sort of prospecting — animals trying to figure out the lay of the land, trying to figure out where things are, where the good habitat might be — and ranging more widely than they would’ve previously.”

Banuli said that when animals return to no food, water or shelter, they will turn this exploration toward new habitat.

However, “if burned areas get rain, they can start growing vegetation very quickly and provide food and water for wildlife. Even the burned trees can be useful for cover, roosting, and in the spring, for cavity nesting birds,” he added.

What happens often comes down to what the fire leaves behind.

“Fire often doesn’t just create this kind of blank slate of nothingness,” Jones said. “There are certainly cases where that might be the way that it looks. But often, fire generates a lot of variation in the forest conditions or the ecological conditions.”

In these cases, “pyrodiversity begets biodiversity,” he added.

“Sometimes fires can generate a really rich kind of template for species to then repopulate,” he said.

Where there’s a lot of variation, it’s described as a mosaic with a patchwork of burned and unburned areas. In these mosaics, the greater diversity of habitat leads to a greater variety of species returning to areas impacted, he added.

With the example of elk and deer, fire can sometimes create a positive opportunity for the ungulates with “young and vigorous vegetation regrowth” that is nutrient-dense, while at the same time, reducing the amount of physical cover they have to hide from predators, he said.

“Fires that create sort of that mosaic of both open areas that are going to have that good browse habitat with what they can eat, as well as refuges that are unburned and create that cover from predators can be helpful for those species,” Jones said.

How are the Meeker fires impacting wildlife?

Earlier in August, Meeker was surrounded by wildfire as two lightning-ignited blazes took off. While the Elk Fire is fully contained at 14,518 acres, the Lee Fire has reached 137,755 acres as of Friday morning with 76% containment.

“The Lee Fire in Rio Blanco County is mostly going to impact winter seasonal habitat for deer and elk, so currently, it hasn’t impacted them until they show up this winter,” Banuli said. “Rabbits and other small mammals may have been more impacted directly from the fires since they don’t migrate, but it really depends on whether or not there are still patches of vegetation that didn’t burn.”

The region’s avian species should be less impacted as nesting, hatching and fledging have already occurred for the most part, he added.

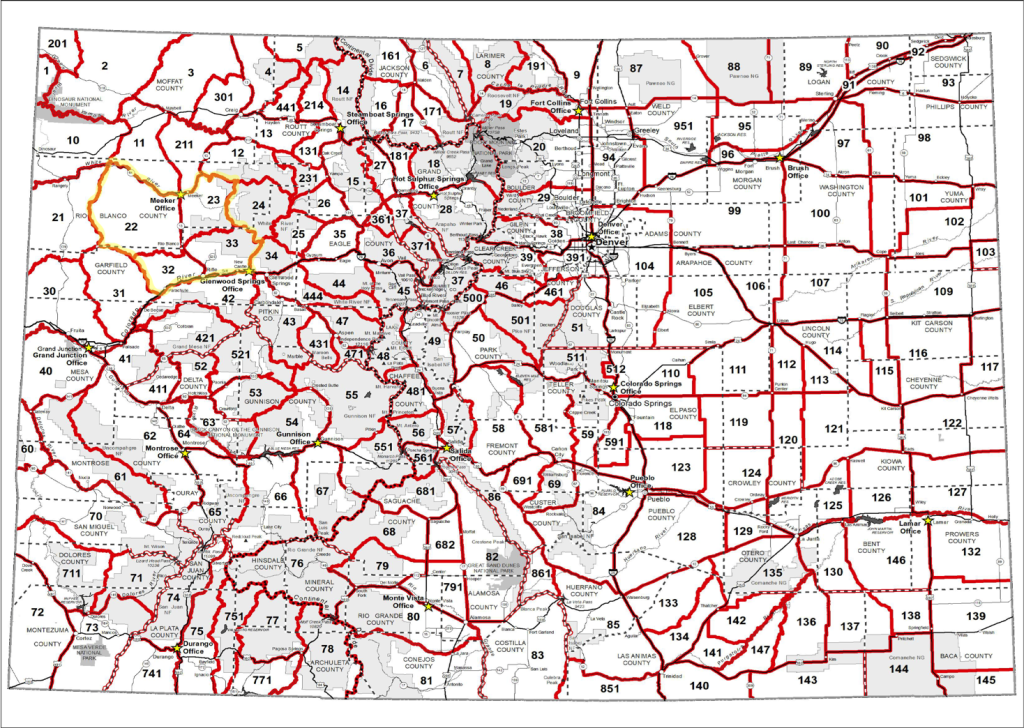

Parks and Wildlife will be offering hunters voluntary refunds for licenses for the upcoming deer, elk and bear seasons within four management units impacted by the fires. The units — 22, 23, 32, and 33 — span portions of Rio Blanco and Garfield counties between Meeker and Glenwood Springs.

The 7,845 hunters with licenses in these units have received emails with their options. According to Rachael Gonzales, a public information officer for Parks and Wildlife, these hunters can turn in their license for a refund up until the season starts.

“No hunting opportunities are closed,” Gonzales said. “This is being given to hunters due to limited or no access into portions of Game Management Units associated with the Lee Fire, while active fire control measures are being taken.”

Currently, it’s difficult to determine what the long-term impacts will be on license numbers in the region, Banuli said.

Hunting seasons are one way that Parks and Wildlife monitors the state’s wildlife populations. It also conducts winter flights to determine ratios of males to females, young survival and model population estimates. It also collects species information using GPS tracking, habitat use and survival data.

Combined, this data is used “to compare where we are in relation to herd management objectives” and determine impacts related to events like drought, severe winters, and fires, Banuli said.

Currently, he said the wildlife agency also has deployed cameras “to try to determine all the species of wildlife that may be using a particular burned area.”

What happens to species living under water?

While the impacts of fire on wildlife that depend on ecosystems like forests, rangeland and grasslands are perhaps more obvious, those living under the water can also be affected.

“In some cases, fires are severe enough and close enough to a stream that fish mortality can be observed due to warming of the stream,” said Ben Felt, a senior aquatic biologist in Parks and Wildlife’s northwest region. “More commonly, the impacts to fisheries occur following a fire when rain falls on fire scars and carries ash, sediment, and debris into a creek.”

While the ash and debris can impact water quality and cause fish mortality, so can the loss or degradation of habitat from these events, like mudslides.

For the most part, when Parks and Wildlife is monitoring fires, it is looking to protect native cutthroat trout populations, Felt said.

“Cutthroat trout populations are especially vulnerable due to many of the populations being located in small headwater streams,” he said. “Based on the small size of these streams, impacts following a fire can have population-level effects.”

This week, the state wildlife agency, with staff from the San Juan National Forest, evacuated 266 cutthroat trout from the path of the Stoner Mesa Fire west of Rico. The fish were captured using electrofishing, where a light dose of electricity is applied in the water, which briefly stuns fish and allows for their capture. From nets to buckets, the captured trout were then driven to the hatchery.

At Thursday’s Parks and Wildlife Commissioner meeting, Reid Dewalt, the agency’s deputy director, said the fish, which represent a portion of this rare lineage of native Colorado River Cutthroat Trout, were moved 165 miles north to the Roaring Judy Fish Hatchery near Gunnison.

“We’ll keep them closely monitored until conditions are stable on the ground and we’re able to return them to the wild,” Dewalt said.

In the northwest, the agency “actively monitors fires throughout the region and regularly assesses the risk to fisheries and the potential for fish salvage operations in situations where fires present a threat to especially valuable fishery resources,” Felt said.

What increasing wildfire danger could mean for wildlife

Animal survival could change as climate change alters historic fire patterns and intensity.

“I would guess that fire survival probably will decrease as fires become more destructive in areas or more intense in areas where they previously were not,” Jones said. “You’re going to have species that are naive to fire and less adept at escaping it and surviving it.”

He said this has prompted ecologists to evaluate questions like: “What does this mean in an era when we have changing fire regimes that are fire regimes that are changing really quickly? Are animals going to be less prepared to survive those fires? Is it going to be sort of these mass selection events where you have really rapid evolution of traits that allow animals to survive fire because they’re being exposed to this really significant selective force?”