How Colorado Parks and Wildlife is using dogs to try and reduce conflict with bears

The wildlife agency is expanding its K-9 program, using dogs for endangered species work, law enforcement, detecting wildlife and more

Colorado Parks and Wildlife/Courtesy Photo

In Colorado, conflicts between bears and humans have been on the rise, pushing Colorado Parks and Wildlife to search for new, innovative solutions.

“Bear conflict is one of the toughest parts of a wildlife officer’s job,” said Ian Petkash, a former Parks and Wildlife district wildlife manager in South Park.

Petkash — and his K-9 partner Samson, a Belgian Malinois — were recently promoted to lead Parks and Wildlife’s new K-9 program, which, among other things, will aim to provide wildlife officers with another four-legged tool to reduce human conflicts with bears.

While Petkash had dreamed of becoming a wildlife officer with a K-9 partner since he saw them featured on a game warden TV show as a kid, he was even more motivated once he became a wildlife officer with Parks and Wildlife in 2013 and began dealing with bear conflict in the Lake George area in South Park.

“Bad bear behavior basically always comes down to bad human behavior,” Petkash said. “Bears are incredibly intelligent. They make very strong associations, and so when they are getting food rewards from folks, it kind of locks in that behavior.”

Once bears learn to exploit humans for food, the animals can become dangerous — and the options for wildlife officers are fairly limited.

One option is to relocate the bears. Last year, Parks and Wildlife relocated 68 bears following conflict. However, this often has “low success” as bears will often return to their home range, Petkash said.

“Their homing tendencies are incredible,” he said. “I’ve had bears that we moved over 200 miles and then showed up on the same doorstep three days later.”

Another option is for the bears to be killed. Last year, 98 bears were euthanized in Colorado. Petkash described those outcomes as “the darkest days in a wildlife officer’s career.”

“So, I wanted to figure out new tools, something innovative, something that you know we could add to our toolbox to help keep both people safe and keep bears safe,” Petkash said.

With his love of dogs and desire to have a K-9 partner at Parks and Wildlife, Petkash naturally began looking into the use of dogs, which have been used extensively across Europe and North America for reducing conflict.

Building Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s K-9 program

Around 2019, when Petkash was doing this research, Parks and Wildlife had a small K-9 pilot program comprised of two wildlife officers and K-9s. The program was looking to determine whether dogs could be a valuable asset in wildlife management.

The pilot program started in 2015 with Sci, a Dutch Shepard, and Phil Gurule, a wildlife officer based in Colorado Springs. Parks and Wildlife had not had a K-9 officer since the 1980s. While Sci retired in 2024, the dog was trained as a more traditional law enforcement K-9 — aiding in investigating poaching and criminal incidents, wildlife detection, and more.

Cash, a black lab, and Brock McArdle, a wildlife officer in Fort Collins, joined the program in 2016. Cash is trained similarly but also has been certified in specific wildlife odors and has helped Parks and Wildlife biologists with endangered species surveys for boreal toads and black-footed ferrets.

Parks and Wildlife’s K-9 officers are trained at a minimum to detect deer, elk, pronghorn, moose, bears, mountain lions, birds, waterfowl and fish.

“They’ve got an incredible ability to differentiate odors,” Petkash said on a March 2025 episode of Parks and Wildlife’s Colorado Outdoors podcast. “When we smell a pot of chili, we smell a pot of chili. When a dog smells a pot of chili, they’re smelling all those different ingredients. … (Dogs) live through scent.”

In 2019, Petkash was authorized to get his own K-9 partner, Samson, and set out to determine whether the agency could use dogs to assist with Colorado’s high volumes of bear conflict.

When Samson and Petkash are called in to assist with bear conflicts, they perform what is called a “hard release,” where they haze the bear to create negative associations at the conflict site. This includes using various hazing methods, including barking and other loud noises, paintball guns, rubber buckshot as well as chasing the bear away.

“We’re using that aversive conditioning to reinstill the fear of humans that bears naturally have and teach the bear that the location, the human food source, is dangerous,” Petkash said.

This allows the bears to stay within their home range but teaches them to avoid and fear humans and stop seeking human food sources.

Petkash said they experienced “solid results” — in line with what other agencies and research projects saw — where in a high percentage of cases, they stopped seeing conflict with certain bears.

Despite the success Petkash and Samson found, using dogs is not a panacea for resolving bear conflict, but rather another tool in the wildlife officer’s toolbox, Petkash said.

It works best for bears that are “early in their conflict career,” Petkash said.

“If you’re able to deploy this with a bear that is in the beginning of losing its fear of people, just getting its first food rewards, we’ve had extremely good success,” he said. “But if you’re trying to deploy this tool on a bear that has received years and years of food rewards — it has totally lost its fear of humans, which has been totally overridden by all those calories that it’s getting — you typically have less success on those bears.”

Getting more dogs in the wildlife agency

The success of this work led Parks and Wildlife to fund a new K-9 program, which will be fully staffed with six wildlife managers and K-9 officers across Colorado next year.

In addition to McArdle and Cash who are deployed in the northern Front Range region, as well as Petkash and Samson in the central Front Range, two other officers were selected.

Officer Mark Richman will be deployed in the central Western Slope regions, covering portions of Eagle, Pitkin, Garfield, Gunnison, Mesa, Delta, Saguache and Hindsdale counties. Officer Ryan Lane will be deployed in the southwest.

The selection and training process for Richman’s and Lane’s K-9 partners began in late July and will take six to eight weeks. Currently, the duos are in a “bonding phase” where the dogs and officers build a “foundation for a good working relationship,” Petkash said.

After that, they will start a handling course and seek certification through the National Police K-9 Association.

All the K-9 officers for Parks and Wildlife are, or will be, trained and certified to assist not only with bear conflicts, but also law enforcement work, wildlife odor detection, evidence search, and “man tracking” for search and rescue assistance. Another important role they fill is in education and outreach.

“The dogs serve as great ambassadors for our agency and our mission,” Petkash said.

While breed plays a role in which dogs are selected, Petkash noted on the podcast that it has more to do with their personalities.

“Breed is not as important as evaluating the specific dog,” he said. “We’re going to be looking for high work drive, high prey drive dogs who we feel confident are going to be good candidates.”

Petkash refers to his dog, Samson, as “my knucklehead” who loves to work.

“When I’m putting my uniform on every morning, he starts doing zoomies because he knows he’s getting to go to work,” Petkash said. “When we get home and his harness comes off, he goes full bore, off duty.”

The agency plans to select officers for the remaining regions — which will cover the remaining parts of northwest and southeast Colorado — next year.

Petkash said it was “pretty darn neat” to see the program finally get to the place where it can grow.

“Getting Sampson and being able to have a partner that rides in the truck with me every day, that’s been the most rewarding part of my career by far,” he said.

Outfitted: Camping standouts

Camping in Colorado is an exercise in balance between rugged and comfortable, minimal and well-prepared. Each of these six items bridges that gap in their own way. Whether I’m chasing alpine sunrises or just soaking in some starlight next to a lake, this gear has earned a place in my standard kit.

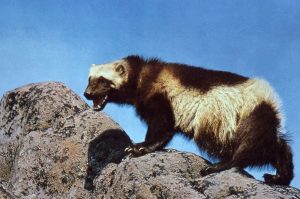

Aspen area included in ‘release zone’ for wolverine reintroduction

The Aspen area has been included in one of three general release zones for the reintroduction of wolverines into the state, according to preliminary information from Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s developing plan.