Will this year be boom or bust for Colorado’s grasshopper populations?

A look at why grasshopper populations can be so variable from year to year and what happens when they take over

Lance Cheung, U.S. Department of Agriculture/Courtesy Photo

Last summer, parts of Colorado experienced significant grasshopper infestations, causing economic and ecological damage in the impacted areas. This year, it’s a slightly different story for the insects that are highly sensitive to seasonal changes.

Melissa Schreiner, an entomologist with the Colorado State University Extension, said current observations and reports show variable populations of grasshoppers based on how spring conditions affected different regions in the state.

“If early-season conditions were drier and warmer than average — particularly in semi-arid rangelands — we may see continued elevated populations, especially in places where the previous year’s outbreak resulted in high egg-laying rates,” Schreiner said. “However, in regions that received ample moisture or experienced late cold events this spring, we anticipate more subdued populations.”

Some areas are reporting “problematic” numbers again this year, Schreiner added.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service conducts surveys of both rangeland grasshopper and Mormon cricket populations in Colorado and 16 other Western States. While grasshoppers and Mormon crickets have their differences, both species have similar detrimental impacts during population booms, leading the agency to manage them under a single suppression program.

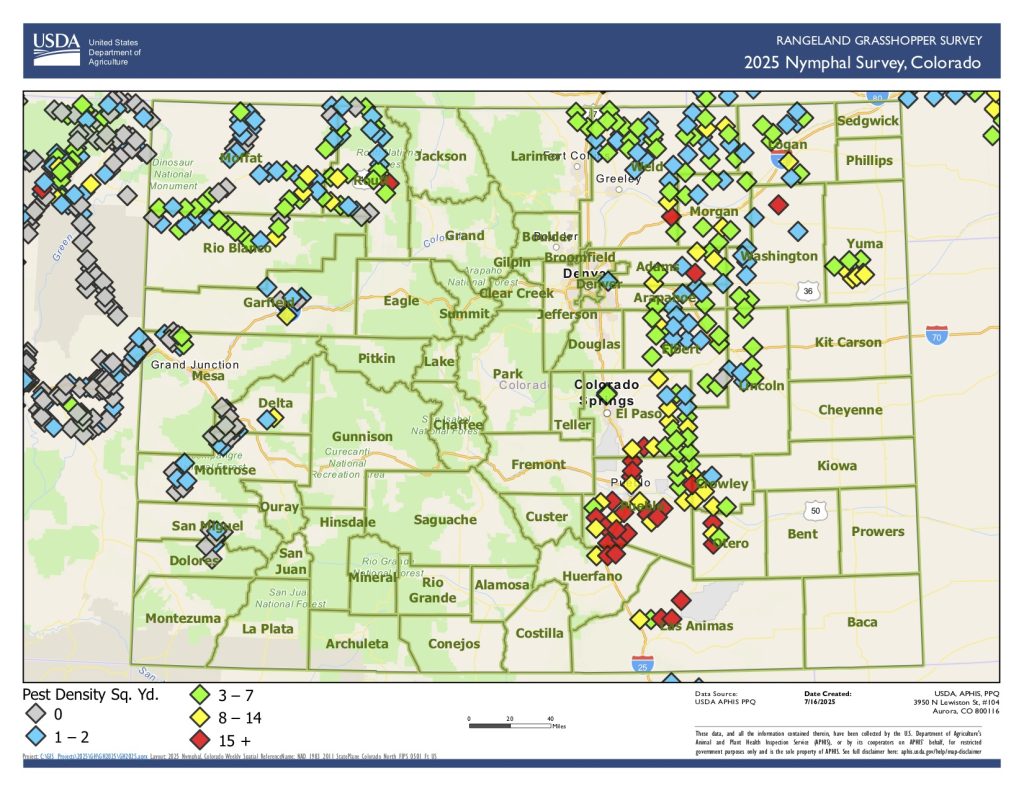

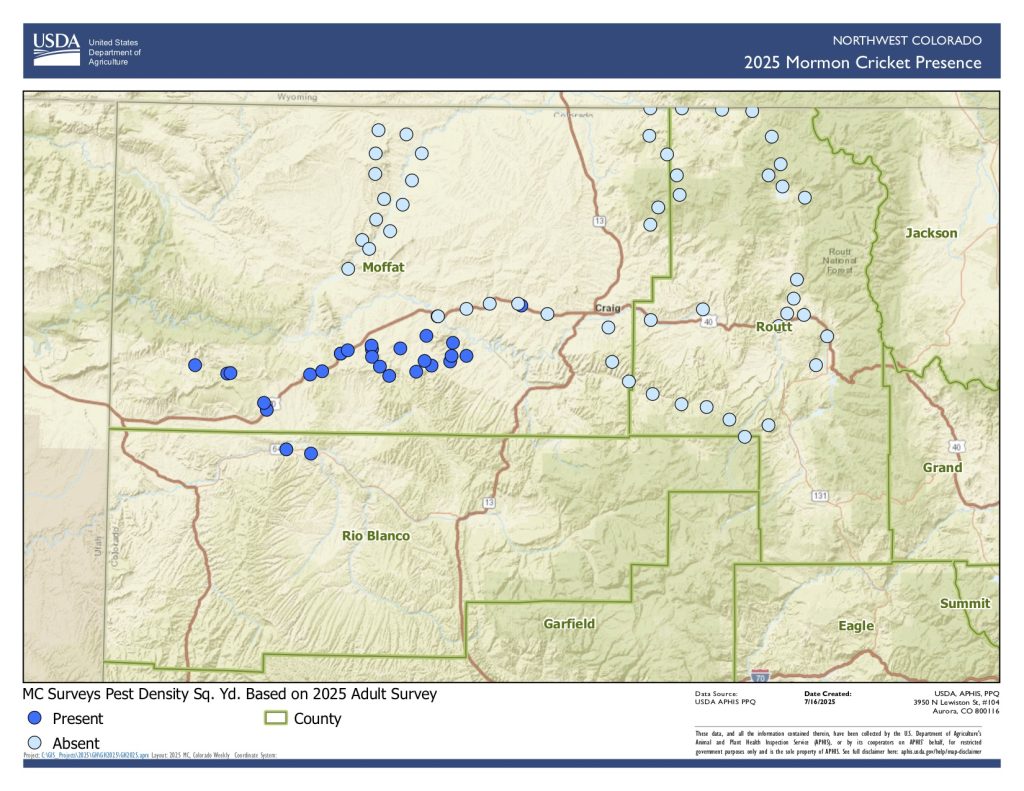

Based on the service’s July 16 survey of Colorado, the density of rangeland grasshoppers is highest in Pueblo County and the surrounding counties, and in small pockets of Adams, Morgan, Washington and Routt counties. The survey also indicates a presence of Mormon crickets in parts of southern Moffat County and northern Rio Blanco County, similar to the areas where the insects took over in 2024.

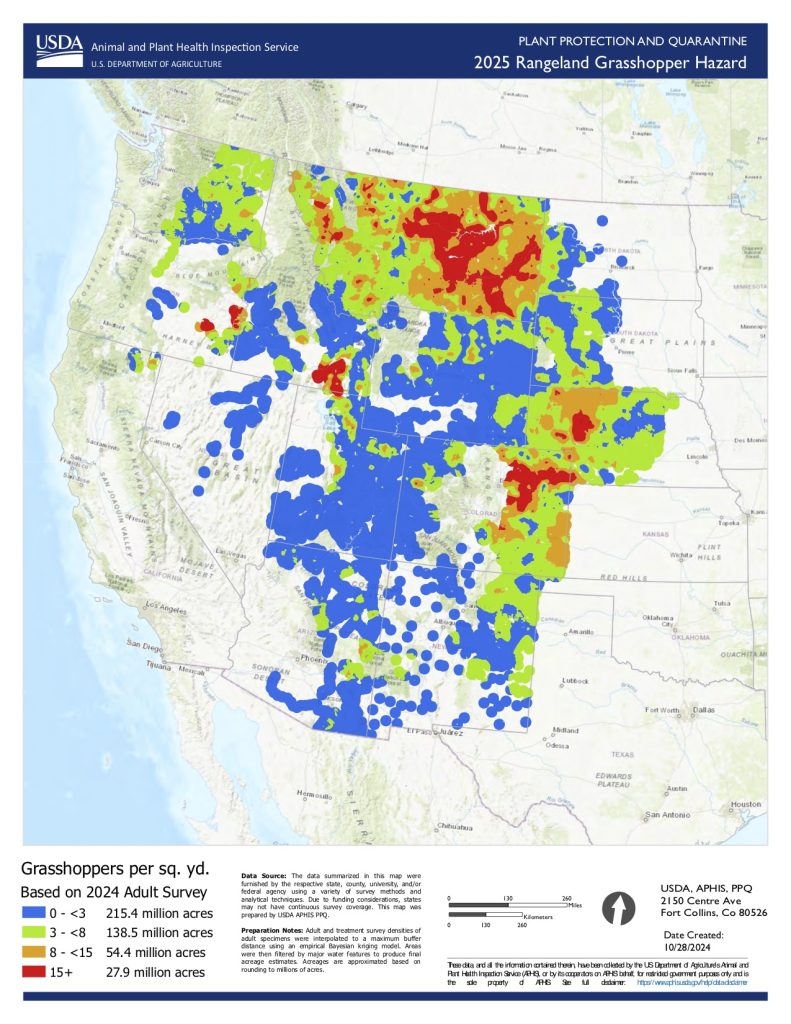

The federal agency also provides forecasts for each summer based on surveys of the adult populations conducted in the fall. The 2024 survey predicted that most of Western Colorado would see moderate populations this year.

However, forecasting populations of the invertebrates can be challenging because so many factors impact their success and failure.

“Under favorable environmental conditions, grasshopper populations can rapidly surge from low, background levels to damaging densities within just one or two seasons,” said Francisco Garcia Bulle Bueno, the Butterfly Pavilion’s director of research and conservation. “This sensitivity to climate, particularly temperature and precipitation, makes them one of the most responsive groups to short-term environmental change.”

What leads to outbreaks like last year?

Conditions in Colorado last year led areas, predominantly along the Front Range, to experience one of the worst infestations of grasshoppers in recent years.

“Grasshopper outbreaks are generally driven by a combination of weather conditions, landscape-scale ecological factors and their biological life cycle,” Schreiner said. “In years with unusually warm, dry springs followed by hot, dry summers — as we experienced last year — grasshopper survival tends to be high.”

Warmer and drier conditions have several effects on the population. According to Schreiner, these conditions can cause earlier hatch success and development, which in turn gives them longer to feed and grow and can also reduce natural predators and pathogens that typically suppress population growth.

Additionally, grasshoppers are highly responsive to landscape-scale changes.

“When vegetation is sparse and stressed across a large area, particularly in rangelands and adjacent croplands, grasshoppers will aggregate, compounding pressure on multiple land types,” Schreiner said.

Conversely, the opposite conditions can have negative impacts on populations.

“Cool, wet springs are the most consistent suppressor of grasshopper populations alongside extreme cold periods in the wintertime,” Schreiner said, adding that this can include sudden spring freezes. “Extreme cold with little snow cover or mid-winter thaws followed by refreezing — can also significantly reduce the number of viable eggs come spring.”

Additionally, plants tend to be more abundant when there is more moisture. More plant growth helps to disperse grasshoppers across the landscape, reducing the concentrated feeding pressure and damage seen when populations are high and vegetation is sparse during hotter and drier periods, Schreiner said.

One of the reasons the insects are so sensitive to spring conditions is that many species of grasshoppers only reproduce once a year.

“Unlike some crop pests with a few localized generations per year, many grasshopper species overwinter as eggs and have only one generation per year, making population forecasting tied closely to a single season’s conditions,” Schreiner said.

However, female grasshoppers lay hundreds of eggs during that single season, so when conditions align for survival, it causes these population explosions.

Grasshoppers’ reliance on these large-scale environmental cues for population success tends to give them “much more dramatic boom-and-bust cycles than other invertebrates,” Schreiner said.

While the West commonly experiences the conditions that lead to population success, Garcia Bulle Bueno warned that the long-term impacts of drought could eventually have a negative impact as well.

“The current hot and dry summer in Western Colorado could have mixed effects,” Garcia Bulle Bueno said. “Warm and dry weather can accelerate development and increase mobility, leading to more visible aggregations. However, if drought conditions become too severe, they may also reduce food availability and increase mortality, especially for late-stage nymphs and adults.”

Nymphs are young grasshoppers.

Extremely dry soils can impact the vitality of eggs laid later this year, so even if conditions this year intensify grasshopper activity in the short term, the severity and length of drought conditions could limit long-term reproductive success, Garcia Bulle Bueno added.

Predicting what each year will bring for grasshoppers is challenging and can depend not only on these environmental factors, but also on the species of grasshopper, Garcia Bulle Bueno said. There are nearly 600 grasshopper species in North America — only 12 of which are considered pests, according to the Department of Agriculture. Colorado is home to at least 133 of these species.

This underscores the need for additional research on invertebrate species, which he says are often “understudied, misunderstood, and underappreciated,” Garcia Bulle Bueno said.

“Understanding the drivers behind their population booms or declines helps us make informed decisions about rangeland management, agriculture and biodiversity conservation,” Garcia Bulle Bueno added.

What harm can grasshoppers cause?

Periodic outbreaks of either grasshoppers or Mormon crickets can cause damage to grass and vegetation, which can have a ripple effect on plant growth, seed production, livestock forage, rangeland nutrient cycles, water filtration and more, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Grasshoppers should be understood as a landscape-level phenomenon, and complex of pests, especially in the Western U.S., where vast stretches of rangeland, dryland crops and open spaces promote ideal conditions for large-scale movement and breeding,” Schreiner said. “When the weather lines up just right — typically after back-to-back dry years with a warm spring with a lot of cold weather — they can become a dominant herbivore in the landscape.”

This has implications for ranchers, conservationists and native plant ecosystems in both urban and rural areas, added Schreiner.

While Colorado does not currently have a program to deal with grasshoppers and Mormon crickets, the Colorado State University Extensions offer help in managing the pests and the U.S. Department of Agriculture funds some suppression treatment options on rangelands that are heavily impacted.

What good are grasshoppers?

Despite the damage caused, the Colorado State University Extension refers to grasshoppers as “the most important insect pests in Colorado.”

With healthy population numbers, grasshoppers have a critical ecological role.

“They are primarily herbivores, helping regulate plant communities and contributing to nutrient cycling through their feeding and waste,” Garcia Bulle Bueno said. “They are an important food source for birds, mammals, reptiles and other insects, playing a key role in ecological food webs.”

Thus, these year-to-year fluctuations in population “can have cascading effects on pollination, food webs, and ecosystem health,” Garcia Bulle Bueno added.

Wildfire in Missouri Heights prompts evacuations, burns 115 acres as of Sunday night

A wildfire broke out Sunday near Missouri Heights that prompted temporary evacuations and burned an estimated 115 acres, although no injuries or major structural damage were reported.