Ancient enchantment: Walled cities of Europe

ALL |

We were driving uphill, winding our way through swirling clouds, with no real certainty about where we were going. The road was narrow, the pavement crumbling. There were no road signs, except one that appeared when I was just about to give up and turn back – a small sign that said “Marvão” in rough letters, with an arrow pointing the way. Marvão was my goal, so I kept going.It wasn’t clear that going to Marvão was a good idea. Quite the opposite, in fact.My wife and I were living in Spain that winter. We’d shivered through a bitterly cold December in our freezing Madrid apartment after the furnace broke down and stayed broken for weeks. Every day, when I passed the furnace room, I’d look in and see one or two men, hands in their pockets, staring at a pile of ancient, greasy furnace parts and shaking their heads.

We fled Madrid two days after Christmas, with the intention of spending New Year’s somewhere, anywhere, on Portugal’s Atlantic Coast. We started with high hopes, but almost before we were out of the city, my wife succumbed to an attack of chills and fever. We pushed ahead – this was our vacation, damn it! We spent a bad night in a bad hotel on the road and now, late the next morning, less than halfway to the coast, I’d turned off the highway and was driving up into the Serra de São Mamede mountains.It was clearly not a good idea. But I’d read somewhere that Marvão was an ancient walled city and I wanted to see it. For the moment, my wife was too sick to object – but if she got any worse, she’d be too sick not to object. Strongly. And she’d be very right. I kept telling myself I would turn around as soon as I found a wide spot in the road.And then we broke through the clouds, into the sunshine. And there was Marvão. A walled city. Tiny. Perched on the top of the mountain.I had hoped for a restaurant and a hot lunch for my long-suffering wife, but at first glance I was certain there’d be no restaurant there. Marvão seemed abandoned, no signs of life. The gate in the fortress wall looked too narrow for a car to get through, but I kept driving, held my breath, and suddenly we were inside, twisting upward through narrow streets, between old stone buildings.And in one of those buildings we found a wonderful hotel, part of Portugal’s national alliance of “pousadas.” We had a miraculous long lunch, sitting near a roaring fire, looking out across the countryside from our mountaintop fortress. We knew we were driving no farther that day. There was no problem getting a room – tourism was low in the Serra de São Mamede in the dead of winter. We spent hours by the fire, drank wine, went to bed early and slept late.We found blessed sanctuary in that walled city, but for me the important moment was driving the winding road up through the clouds and emerging to see the fortress city on the mountain just ahead. It stood alone, isolated, self-contained. Wrapped within its walls, the tiny city on the border between ancient kingdoms was protected – once, from armies, now, from change, from the world outside its walls. More than the sight itself, the emotion of that moment is still clear in my memory.

My mystical fondness for walled cities got a bit dented a few years after our visit to Marvão, when we had the misfortune to visit Carcassonne in July. As we drove toward it, the city floated over the countryside, a vision from history. But parking lots extended in all directions from the city, the roads were clogged with tour buses and once inside the walls we were surrounded and buffeted by mobs. Every store sold tourist trinkets or housed a Museum of Torture.It was impossible. We fled the city, agreeing that, perhaps in February, it might be haunting, if you could stand the cold and ice.That was half a dozen years ago and it put me off walled cities for a while.But last summer, I couldn’t resist the call of another walled city that had danced in my mind’s eye for many years: Dubrovnik. I remember how my heart sank when I read about the siege and shelling of Dubrovnik by the Serbs in 1991. But most of the damage has been lovingly repaired, and I couldn’t stay away any longer.In fact, Dubrovnik, though extraordinary, was just one of three walled cities we visited on that trip to Croatia and Montenegro’s Dalmatian Coast.The first of the three was the least likely: the town of Kotor in Montenegro.We discovered Kotor, like Marvão, almost by accident.

Taking bad advice from a travel story in a major newspaper, we had booked a room in the seaside town of Herceg Novi. When we got there, the streets were almost impassable, jammed with crowds of tourists and enormous tour buses. My wife took a quick look at the recommended guest house and canceled our reservation on the spot.We fought our way out of town and headed down the coast. A single line in that same unreliable newspaper story had mentioned the town of Kotor and the name of a hotel there. We decided to take a chance.The drive was harrowing. The road was narrow and winding, without shoulders or guardrails, jammed with cars and buses, all driving erratically. And yet, the scenery was so spectacular that the drive was worth the danger. The Bay of Kotor is vast, with rugged mountains rising almost directly from the water. The coast is dotted with small towns and the water with tiny islands, some so small that they each hold only a single, ancient monastery.And, deep within this stunning, craggy scenery lies the walled city of Kotor.

A fortress was built on the site by Emperor Justinian I in the year 535 after his armies seized the land from the Goths. The city was ravaged by the Saracens in 840, taken over by the powerful Venetian Republic in 1420, twice assaulted by Ottoman armies, savaged by the plague and almost destroyed by two earthquakes. Goths, Saracens, Venetians, Ottomans, plague, earthquakes … history echoes through the old city.These days, with a population of some 25,000, the modern city of Kotor has spilled far outside the walls in a jumble of nondescript buildings. But once you pass through the gate into the small old town, where no cars can go, you are in an ancient maze of narrow cobblestone streets, twisting and turning through dead ends and alleys and sudden, unexpected open plazas. And, for all the weight of its history, the old city is very much alive. Those narrow streets bustle with energy – yes, there are tourists, but there is also real life. Laundry hangs out to dry on clotheslines stretched between buildings, dogs sleep in the sun, cats scurry through the shadows, children chase pigeons across the square.Our hotel was plain, clean and cheap. No one spoke English, but we cobbled together enough French, Spanish, gestures and grunts to make ourselves understood. We checked in and hurried to find a cafe where we could sit and enjoy the sense of shelter, embraced by stone walls nearly 50 feet thick.That night, we wandered streets thronged with visitors – some from Western Europe, many from Eastern Europe and just about none from any English-speaking country. With the exception of one family in a restaurant, we did not hear a single word of English spoken in our days in Kotor. As happened more than a decade ago in Marvão, a random choice had turned into a wonderful discovery, a walled city whose walls still defend it. The walls that protected Kotor against Ottoman armies now shelter old Kotor from its own modern success. It’s true, some shops sell modern trinkets and rock music can echo through the streets late at night, but the old town’s character remains intact within those walls. The next walled city on our trip was Korcula, on the island of the same name, off the coast of Croatia, a day’s drive north of Kotor.

Like Kotor, Korcula has centuries of history: The Romans took it from the Greeks, the Goths took it from the Romans. Then came the Byzantines and the Venetians. The Venetians held Korcula for centuries, and they were followed by the Austrians, the French, the Russians (who swapped the town back and forth with the French over the course of a decade) and eventually, for a few years, the British. Korcula did fight off an Ottoman assault, but it seems to have succumbed to invaders all too often.All this, perhaps, reveals a different aspect of walled cities. They get their walls because they’re vital spots, worth defending; and for that same reason, they are often attacked – and, often enough, they’re conquered.In fact, just as its history may offer a lesson on the futility of walls, Korcula’s present situation underlines that lesson, because it is, strictly speaking, a formerly walled city. Back in the mid-1800s, the good people of Korcula decided that the walls were too expensive to maintain, that peace was at hand, and that fresh sea breezes might be a good thing – so they tore down almost all of the walls. From some angles, Korcula’s walls and towers still seem formidable. But from other viewpoints, the walls disappear. When you approach the city by ferry from the Croatian mainland, you see the old stone buildings rising from the clear turquoise water, with only the corner towers to mark where the fortified walls once stood. And that view reveals the hidden beauty of walled cities. The buildings cluster, rising higher, block by block, to the cathedral in the center of the town.On shore, you enter the city through a gate in a remaining portion of the medieval walls – walking up a grand stairway that has replaced the old drawbridge across the city’s moat. And when you walk the narrow streets in the heart of tiny Korcula, it feels as if you’re still very much within a medieval walled city. The character of a walled city is created not just by the existence of the walls, but by the way those walls compress the development within. Even once the walls are gone, it is still somehow a walled city. Sheltered and sheltering.

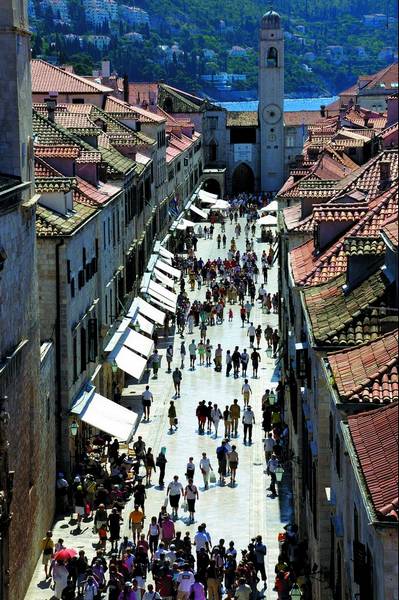

Our final walled city was Dubrovnik, the grandest, most spectacular of all.Dubrovnik is indeed a kind of miracle. It is beautiful, strong and gracious – and even when flooded with tourists, as it is in midsummer, the city’s character remains.Like Kotor, Dubrovnik has spilled far beyond its walls, but once you are within those walls, the rest of the world disappears. The central street – the Stradun – is wide, with generous open squares at both ends. To either side of the Stradun the streets, though straight, are narrow, shadowed by the buildings on either side.And, as in both Kotor and Korcula, here too a declining number of native residents try to maintain a real existence in the face of growing tourism and second-home owners.Again, like the other walled cities we visited, Dubrovnik has a deep and ancient history – but, like the city itself, Dubrovnik’s history is larger, more spectacular. Settled in the seventh century, it eventually became a powerful republic in its own right, a city-state. It was a major maritime power, trading through the Mediterranean and beyond. It rivaled Venice in its wealth and power.Dubrovnik was famed as a city of artists and scholars, wealthy merchants and wily diplomats. In fact, its diplomats managed to strike bargains that kept the city independent for centuries. The Republic of Dubrovnik sometimes paid tribute and taxes to more powerful nations, but it maintained its identity and wealth.Still, diplomacy aside, Dubrovnik’s security over the centuries owed a great deal to its high, thick walls, which were never overcome by an invader in violent battle.

And that brings us to the true miracle of Dubrovnik, its defiance and survival in the siege of 1991, when the Serbian army and navy turned modern artillery and missiles against the city. The Serbs expected the essentially undefended city to quickly collapse, but the citizens of Dubrovnik took shelter within the city walls and refused to surrender.And although Dubrovnik’s major walls were mostly built in the 1300s and 1400s, they proved themselves strong enough to withstand 20th-century high explosives. Solid stone walls 20 feet thick – sometimes more – are not easily destroyed. The siege lasted for months, and the people of Dubrovnik proved themselves as tough as the walls that surrounded them. They lived without water or electricity from October through December.Although the artillery shells couldn’t destroy the city walls, they wreaked havoc within those walls. When you stand on the walls of Dubrovnik today and look out over the city, the signs of the damage are clear. The roofs are a patchwork of the muted, faded colors of centuries-old tiles and the much larger expanses of bright orange new tiles. More than two-thirds of the buildings in Dubrovnik suffered damage from the bombardment. Many were severely damaged; a few were destroyed completely.But Dubrovnik would not surrender. And after months of sporadic bombardments, international pressure finally forced the Serbs to declare a truce and withdraw.The city’s motto is “Libertas” – Freedom. And Dubrovnik still stands proudly free within the shelter of its historic walls.Three walled cities on the Dalmatian Coast. All beautiful, all different. In one, Kotor, the walls hold the modern city at bay. In the second, Korcula, the walls themselves have disappeared, but the city retains its ancient character. And in the third, Dubrovnik, the walls have never failed and the city still shines as a miracle of grace, beauty and courage.

Andy Stone is former editor of The Aspen Times. His e-mail address is andy@aspentimes.com.

Maroon Bells lack water, electricity, and toilets due to budget cuts, staff shortages

The Maroon Bells Scenic Area is short on staff and amenities following funding cuts from the federal government.