Willoughby: Pens, pencils, and penmanship

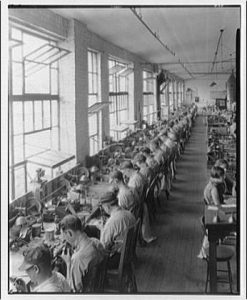

Library of Congress/Courtesy photo

Wading through some correspondence by my great-grandfather from the 1860s-70s reminded me of the changes in handwriting related to the technology. The cursive style of the time is hard to read today, but no more so than my own generation’s cursive. What is also evident is that he used an ink pen where the nib, by varying the pressure, could vary the width, giving greater style elements compared to our present-day ballpoint pens that were introduced in the 1950s.

One of the big changes was in 1884 when the Waterman company began manufacturing the fountain pen. Before, you dipped your pen into an ink well, often. You may have gone to school where the student desks had ink wells or the holes in the desks where there used to be ink wells. Watermen pens were popular in Aspen, but the early fountain pens were not easily filled, with spilled and leaking ink complicating things.

Some fountain pen humor in The Aspen Times illustrates that it was one of the major topics of the day. 1890: “The man who can successfully manage a fountain pen has talent enough to become a Colorado politician.” 1892: “Was the fountain invented by Mr. Fontaine? No, you idiot — the fountain pen was invented by the devil.”

Cooper’s, one of the major Aspen carriers of fountain pens in that period, advertised in 1905 Moore’s improved non-leakable fountain pens. His pitch, “they will not leak on your hands or paper and they carry a guarantee to this effect.” In 1906, they advertised, “Don’t buy a cheap fountain pen, it doesn’t pay.” And in 1908, they were pushing “Conklin’s self-filling pens.” Pens sold for, in today’s dollars, from $67 to $135. (Note: The nibs had gold in them.)

The next advance came in 1902, when Sheaffer patented the ink cartridge. It didn’t go anywhere for a while, but in 1912, Parker came up with a viable cartridge.

The history of pencils compliments the fountain pen. Graphite (lead) pens go all the way back to the 1500s, as did wood-encased pencils. Benjamin Franklin came up with some and advertised them in 1729. Erasers were added in 1856, and the pencils we commonly use today, the yellow ones, began in 1890.

Pencils were far cheaper than pens, but in schools, students often used small, slate chalk boards. The chalk for them were called slate pencils. Chalk dust was annoying and often joked about, but it was less of a problem than spilled ink or ink on fingers.

Aspen’s low-priced stores, one called The Cheap Store, in the 1890s carried pencils, paper, slate boards, and ink. A slate, in today’s dollars, ran $5.88. Many items sold for 10 cents, $2.63 in today’s dollars. You could get two-dozen lead pencils, 30 slate pencils (chalk), four bottles of black ink, or two dozen pen points. Two quires of paper, which was around 50 sheets, also cost 10 cents. The size was not mentioned, but likely around 5 by 8 inches.

The ultimate technology of that period was the introduction of typewriters. There wasn’t a dealer in Aspen, but you could buy Remington typewriters in Denver. There were two typists in Aspen during that period that advertised. They likely had lots of customers because a Remington at that time cost, in today’s dollars, $3,200.

Tim Willoughby’s family story parallels Aspen’s. He began sharing folklore while teaching at Aspen Country Day School and Colorado Mountain College. Now a tourist in his native town, he views it with historical perspective. Reach him at redmtn2@comcast.net.

Willoughby: Pens, pencils, and penmanship

Wading through some correspondence by my great-grandfather from the 1860s-70s reminded me of the changes in handwriting related to the technology.