Willoughby: Gravity at 8,000 feet

Willoughby collection/Courtesy photo

I didn’t have an apple tree to sit under to understand gravity, but living in a skiing and mining town surrounded with steep, sloped mountains introduced me to gravity forces, both positive and negative.

The first lesson came from exploring the town on a bicycle. Living in the downtown area, I thought of the town as one with flat streets. But venturing west on Main Street destroyed that belief: It was — on a bicycle with no gears and eight-year-old muscles — hard work. But returning home instructed me that gravity works for you, too.

There were no falling apples, but winter snow fell down, not up. I didn’t have to exert myself to get to the top of Little Nell, the T-bar pulled me uphill. I, quickly, had to learn to turn since gravity, even with poorly waxed skis, increased my speed QUICKLY.

As my ski skills improved, I took to flying off moguls and the small ski jump on the west side of Little Nell. I didn’t choose to, but I quickly learned that gravity worked whether you were in the air or on the ground, but the angle of landing dictated survival. I also graduated to lifts taking me to the top of the mountain and learned that while gravity was constant, the downhill distance you could cover varied according to slope steepness. I also learned that gravity didn’t have to rest, but my ski muscles needed breaks.

Some finer physics laws were learned as a teenager. In 1965, realtor Hans Gramiger was working on his dream project to build a restaurant on top of the Shadow Mountain rock ridge overlooking town. He bought the mining claim that included that section and would hike from his Main Street office, below, to the top and clear the area. He would dislodge large boulders. With gravity working overtime, some rolled all the way down the slope smashing tree trunks on the way down. The west side was the steepest and, fortunately, there were few homes at the bottom.

That is when I really began to understand avalanches, the most common avalanche areas near town were close to his boulder tracks, avalanches starting at the ridge, then, today and well into the past, made their way all the way to Castle Creek. I also learned that they were more likely to slide if someone, like a Hans on skis, set them off.

The beginning of my driving provided some very important Aspen lessons. Jeeps, then, had brakes that barely worked, especially on steep Jeep roads. Having the Jeep in low gears defied gravity, but the engine had to work as hard as when it went uphill. Jeeps were amazing vehicles, but gravity is constant no matter if you are going uphill or downhill.

Working for the MAA, moving pianos beginning in 1966, instructed me on how to work around gravity. My cousin and I had to move the festival’s grand pianos at the tent up and down the different levels — 1,300 pounds divided by two people would break our backs, but moving one third of a piano at a time with two people defied gravity. We also learned basic physics: how a fulcrum works, watching two truck drivers delivering the Steinways to Aspen, and setting them up with no extra help.

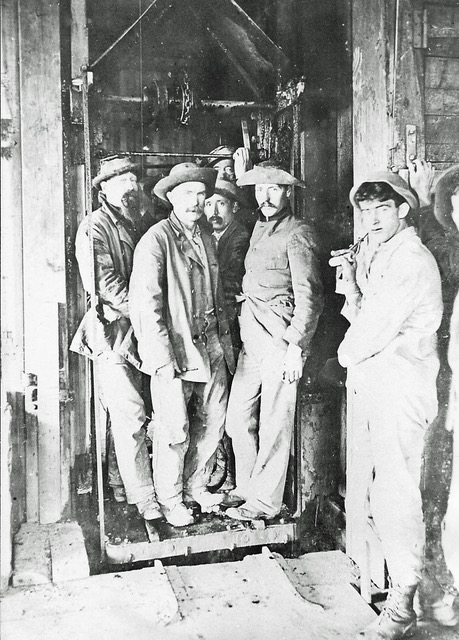

My father educated me on all the ways miners had to overcome gravity. One ore car of silver ore weighed a ton. Hauling it up a shaft hundreds of feet to the surface required engineering and lots of power, and there was (see photo) an easier way to climb to the surface than climbing hundreds of feet of ladders.

Each time a mine went down another 60 to 100 feet (if it had a shaft), they would open a new tunnel at the lower level, drive it some distance and then mine uphill rather than digging down from the above level. Letting rocks roll down to the tunnel below was less work than hauling them all up with muscle labor.

He also explained to me about the mine trams that preceded ski lifts, how they used gravity. The mines were at the top of the trams; they loaded the ore into the tram buckets, and the weight of them, with gravity at work, would make the cable loop move, hauling the empty buckets up the mountain. Since he was involved in building the first lifts, he saw the comparison, hauling skiers up the mountain, so they could take advantage of gravity skiing down.

Tim Willoughby’s family story parallels Aspen’s. He began sharing folklore while teaching at Aspen Country Day School and Colorado Mountain College. Now a tourist in his native town, he views it with historical perspective. Reach him at redmtn2@comcast.net.