Colorado’s reintroduced wolves are moving toward the New Mexico border, though many are sticking to the central mountains

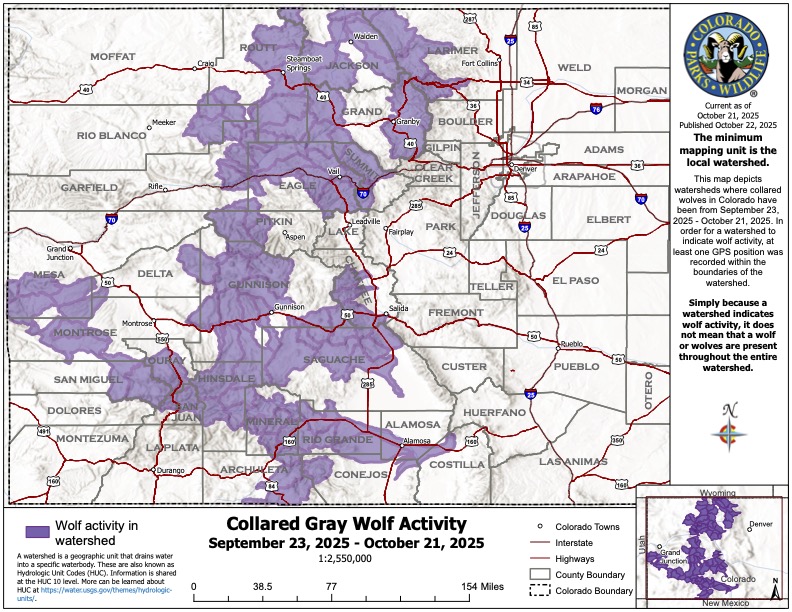

Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s October wolf map highlights where GPS-collared gray wolves have roamed over the past month

Colorado Parks and Wildlife/Courtesy image

Colorado’s collared gray wolves have continued spreading across the Western Slope, with more movement toward southern parts of the state near New Mexico’s border during the month of October.

Colorado Parks and Wildlife’s latest wolf map — which highlights watershed activity from the state’s collared gray wolves between Sept. 23 and Oct. 21 — shows a broad trend of southward migration, with wolf activity recorded in several counties across southwestern Colorado including southern Mesa County, Chaffee, Montrose, San Miguel, Ouray, and others. Wolves also remained active in Gunnison, Saguache, Mineral, and Rio Grande counties from September into October.

In Colorado’s central mountain region, wolf activity remained consistent across several familiar counties, including Pitkin, Eagle, Summit, Grand, Jackson, and Routt counties. Significant activity moved away from watersheds in Moffat, Rio Blanco, and Garfield counties, with slight activity still recorded.

A few watersheds in Colorado’s Front Range — including in Larimer County — also saw new wolf activity over the past month.

If a watershed is highlighted on the map, it means that at least one GPS point from one wolf was recorded in that watershed during the 30 days. GPS points are recorded around every four hours.

Currently, highlighted areas on the wolf map show contact with the borders of Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico — though it’s not confirmed whether any wolves crossed into those states during the month of October.

Luke Perkins, public information officer for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, said the agency does not comment on wolf movements outside of the state.

In addition to being federally protected, gray wolves are a state-endangered species in Colorado, meaning they cannot be harmed or killed for any reason other than self-defense — a protection that can be lost once a wolf crosses into another state.

In its October update, Colorado Parks and Wildlife said the agency “has a memorandum of understanding” with Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona that agrees that any Colorado wolves that cross into those states can be safely recaptured and returned to Colorado. However, this has not yet been put into practice, according to Perkins.

If a wolf crosses north into Wyoming, it can be shot anytime without a license, in line with the state’s laws. This year, three of Colorado’s reintroduced wolves have died after crossing into Wyoming.

Colorado also saw more wolves explore watersheds near tribal lands in October. Colorado Parks and Wildlife has a memorandum of understanding with the Southern Ute Indian Tribe addressing the potential impacts of wolf restoration on the reservation and the Brunot Treaty Area in Southwestern Colorado.

Part of the memorandum states any losses of livestock belonging to the Tribe or Tribal Members proven to be caused by gray wolves will be remedied with “fair and timely compensation.”

Since the agency launched its voter-approved wolf reintroduction efforts in December 2023, 25 wolves have been relocated to the state, 10 have died and four packs have formed.

When wolves are first relocated to Colorado, they become “dispersers,” meaning they leave the pack they were born into to make their own. Currently, Colorado has a higher proportion of disperser wolves than what’s typically seen in more established wolf populations — though it’s expected to decline over time — according to past Aspen Times reporting.

Parks and Wildlife plans to release between 10 and 15 wolves in southwest Colorado this winter, in line with its long-term plan of releasing 30 to 50 wolves within the span of three to five years. This winter’s release could be the state’s last.