Gov. Polis’ budget request for next year includes limits on some Medicaid services, more money for schools

Spending plan for next fiscal year seeks to slow rate of Medicaid spending while continuing to “fully fund” K-12 education

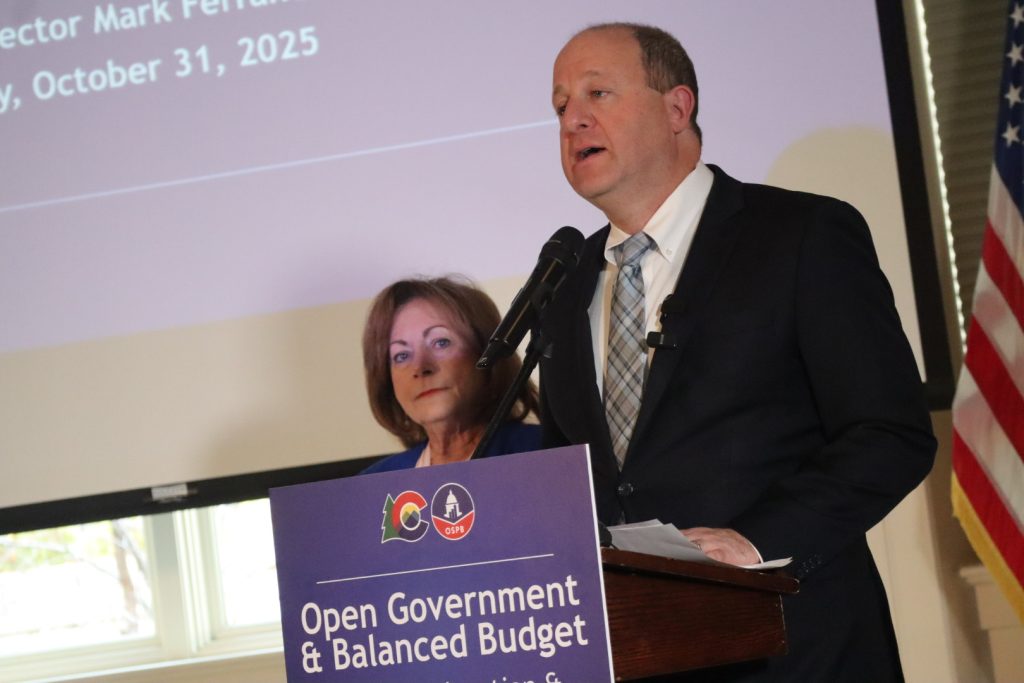

Robert Tann/The Aspen Times

A new budget proposal from Colorado Gov. Jared Polis would slow the rate of state Medicaid spending, including limiting certain services, while continuing to make good on his and the legislature’s promise to “fully fund” K-12 education.

Polis on Friday unveiled his budget request for the 2026-27 fiscal year during a news conference in Denver, where he highlighted the “sustainability of Medicaid” and “investing in our schools” as key priorities.

The budget request will be considered by the Joint Budget Committee, a bipartisan group of lawmakers who will ultimately approve their version of next year’s budget plan, which will need to win approval from the full legislature. That work will begin in earnest in January, when lawmakers reconvene for the 2026 legislative session, and will wrap up in the spring.

Polis said next year’s budget decisions come amid a backdrop of uncertainty from Washington, where the White House has clawed back hundreds of billions of dollars in earmarked funds for Colorado, and Congress has enacted major cuts to tax revenue and social programs.

“This balanced budget addresses those challenges,” Polis said.

Reining in Medicaid

The budget request would increase state spending by 5.6%, with expenditures topping $50 billion. While Polis’ proposal would increase Medicaid spending by $297.7 million, that would account for roughly half of what the program was projected to grow by next fiscal year.

Polis said the state must slow the rate of Medicaid spending to ensure there is money to fund other essential programs, like roads and schools.

Medicaid spending has ballooned in recent years and now accounts for roughly one-third of state expenditures. That’s mainly been driven by an increase in older patients seeking long-term care, as well as benefit expansions and persistent inflation.

“This gets worse if we don’t fix it,” Polis said, adding that if Medicaid spending continues at its current pace, it would “crowd out essentially everything the state does.”

Polis said his budget proposal would not result in loss of coverage for any of the 1.2 million Coloradans who rely on Medicaid, something he said would be “very inhumane” and increase the costs of uncompensated care.

His proposal would, however, scale back certain Medicaid services and benefits.

Examples include limiting billing hours for home health nursing and therapy services. Polis also wants to reinstate a cap on adult dental benefits. Those benefits were capped at $1,500 per person annually in 2023, but that cap was later removed. Polis’ plan would cap benefits at $3,000 per person, and $750 for those enrolled in the Cover All Coloradans program, which provides state Medicaid coverage for undocumented immigrants.

Polis’ budget request also does not include an increase to the state’s reimbursement rate for Medicaid providers next year.

Lawmakers had originally approved a 1.6% provider rate increase for this current fiscal year, but Polis reversed that through an executive order this summer. The reversal was part of Polis’ efforts to close a nearly $800 million budget shortfall caused by the spending and tax cut law passed by congressional Republicans.

Polis said his budget is a “hold harmless” approach because it does not cut the provider rate, something he said would not address the “systemic” increase in Medicaid spending.

More funding for K-12 schools

Polis’ budget plan would continue the commitment lawmakers made to increase public school funding at levels required by the Colorado Constitution. That initiative started in 2024, when lawmakers abolished the budget stabilization factor, a Great Recession-era mechanism that had underfunded schools by around $10 billion over the past 14 years.

They also developed a plan that year to boost K-12 spending by $500 million over the next several years with a new school funding formula.

Polis’ fiscal year 2026-27 proposal would allocate 30% of that additional money to schools, increasing K-12 spending by $276 million, or roughly $413 per student. It would also begin to phase out the multiyear enrollment average used by many schools.

Districts currently have the option to use a four-year enrollment average to determine their student funding count. Polis wanted to eliminate that approach in favor of a current-year student count that would’ve gone into effect this school year.

Lawmakers ultimately passed a counterproposal that would phase out multiyear averaging over time, with districts moving to a three-year average in 2026-27 and eventually a current-year count in later years.

Working amid ‘headwinds’

Other provisions of Polis’ budget plan include beginning the implementation of Proposition 130, which was approved by voters last year and requires the state to transfer $350 million to local law enforcement agencies.

The budget would also increase funding for the state’s universal preschool program by $14.3 million and hold in-state tuition for higher education below the rate of inflation.

Still, Polis said the state will continue to face challenges due to both the ongoing structural deficit and cuts at the federal level.

The structural deficit is the result of the cost of state programs increasing beyond what the state is allowed to spend under the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights, or TABOR, a 1992 voter-approved amendment to the state Constitution.

TABOR limits state revenue growth to the rate of population growth plus inflation, though programs like Medicaid far outpace that rate. Lawmakers this year closed a $1.2 billion deficit and are projected to face an $850 million deficit next year as a result of the structural deficit.

Polis’ budget proposal would eliminate that deficit through measures like reducing the rate of Medicaid spending and privatizing Pinnacol Assurance, the state’s workers’ compensation insurer, which could save the state hundreds of millions. Polis has floated the idea before, but it has proven controversial with lawmakers.

The structural deficit is different from the funding impacts of federal cuts.

“We function under a lot of headwinds,” Polis said. “It’s almost as if the federal government’s making this hard for us here in Colorado.”

That includes federal funds that were earmarked for Colorado but have since been revoked, such as money for emergency management that the state had expected to receive. Colorado will have to spend $7.1 million to backfill that loss, Polis said.

Most of the federal cuts, however, are from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which Republicans in Congress passed this summer. That measure immediately reduced tax revenue for Colorado this year, which led to the nearly $800 million budget hole. Polis and lawmakers closed that deficit during a special session in August.

Colorado will, however, continue to feel the effects of that federal bill for years to come.

New restrictions for receiving Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, for example, will start to take effect in 2027. Cuts to some federal Medicaid and food assistance funding for states will also hit in the coming years, and could cost Colorado hundreds of millions of dollars.

Polis said the state is still awaiting federal guidance on how to implement the new restrictions, such as work requirements, for Medicaid.

“The indications are that we’ll be able to implement it in a way that minimizes the risk of people losing Medicaid,” Polis said.

Mark Ferrandino, Director of the Colorado Office of State Budgeting and Planning, which is part of the governor’s office, said the state is planning to allocate around $15 million this year and next to help counties prepare for and administer those work requirements.