As Colorado mountain towns push for affordable housing, unreliable income data complicates their efforts

Area median income has long been the language of the housing world. Some housing advocates question whether it’s helping — or hindering — their affordability goals.

Ben Roof/Special to the Vail Daily

Spencer and Camille Messer are worried about getting a raise.

The Eagle County couple, who live in a mobile home with their two children — aged 4 and 2 — may finally qualify for a highly coveted, deeply subsidized house through Habitat for Humanity, one of the few options for skirting the area’s sky-high real estate prices.

Looming development plans for their mobile home community may eventually force them to move. Neither wants to go back to renting, and they say a Habitat house may be their best —and only — option for staying in the Vail Valley.

But like most affordable housing in mountain towns, these homes are in short supply, high demand, and often come with strict income limits based on a longstanding, but imperfect, federal metric. If either of them sees even a small pay bump — any more than 2.5% — they may fall outside the cutoff to qualify.

“It’s the strangest type of housing insecurity,” said Spencer Messer, who works as an English teacher and cross-country coach at Battle Mountain High School. “It’s just weird when you have a career and you do as many things as you can to better yourself … that theoretically should put us in a better position to try to buy something.”

“We have to be cautious,” said Camille Messer, a part-time nurse at Vail Health, “about making sure that we’re not making too much money.”

As mountain communities race to dig themselves out of an affordable housing crisis, the range of housing needs is growing across a broader income spectrum.

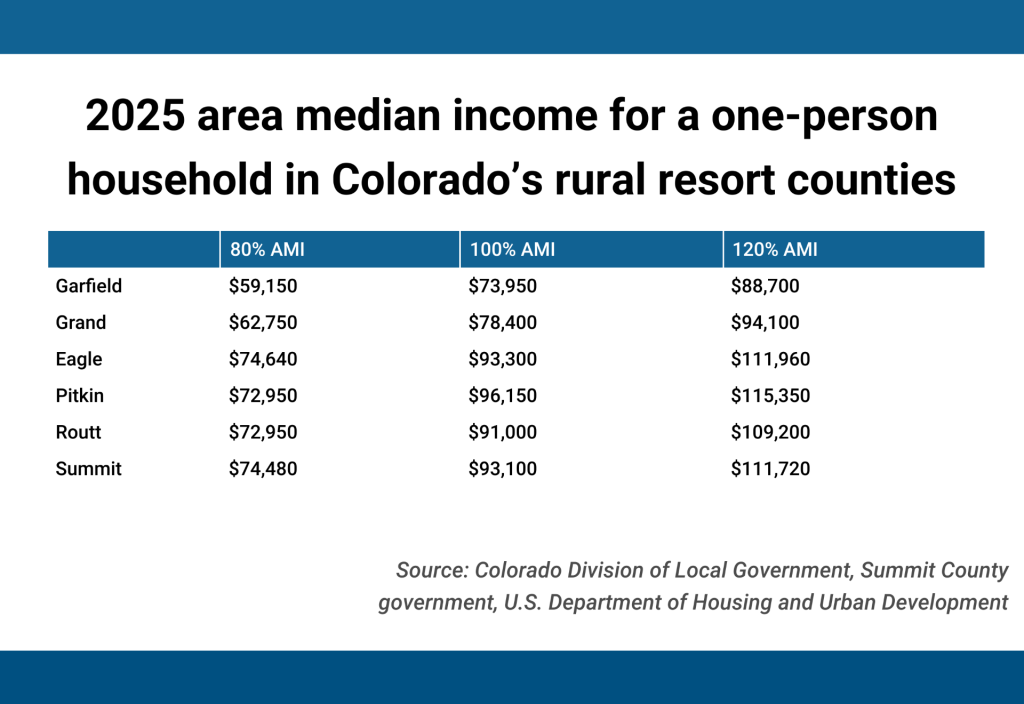

For housing providers, that often means looking at their county’s area median income, which is calculated each year by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and meant to represent the midpoint for earners in that community. That data is also typically used to set both price and eligibility for affordable housing projects.

But in Colorado’s High Country, local leaders say the data can be easily skewed.

“In a community like ours, where you have very, very high incomes and very, very low incomes, it’s not a reliable indicator of where the majority of the community actually is,” said Tamara Pogue, a Summit County commissioner who often works on housing policy.

Sunrise Rundown: Headlines. Breaking News. Local Updates.

What’s happening in Aspen, in one click.

Sign up for the Sunrise Rundown at AspenTimes.com/newsletter

Rural resort areas have smaller sample sizes and larger wealth disparities. Median income figures also include not just wages but investment earnings and retirement income, which can further tilt the numbers toward higher earners. And with much of the workforce in industries where they can make tips and overtime pay, and face slow and busy months, their income can often fluctuate throughout the year.

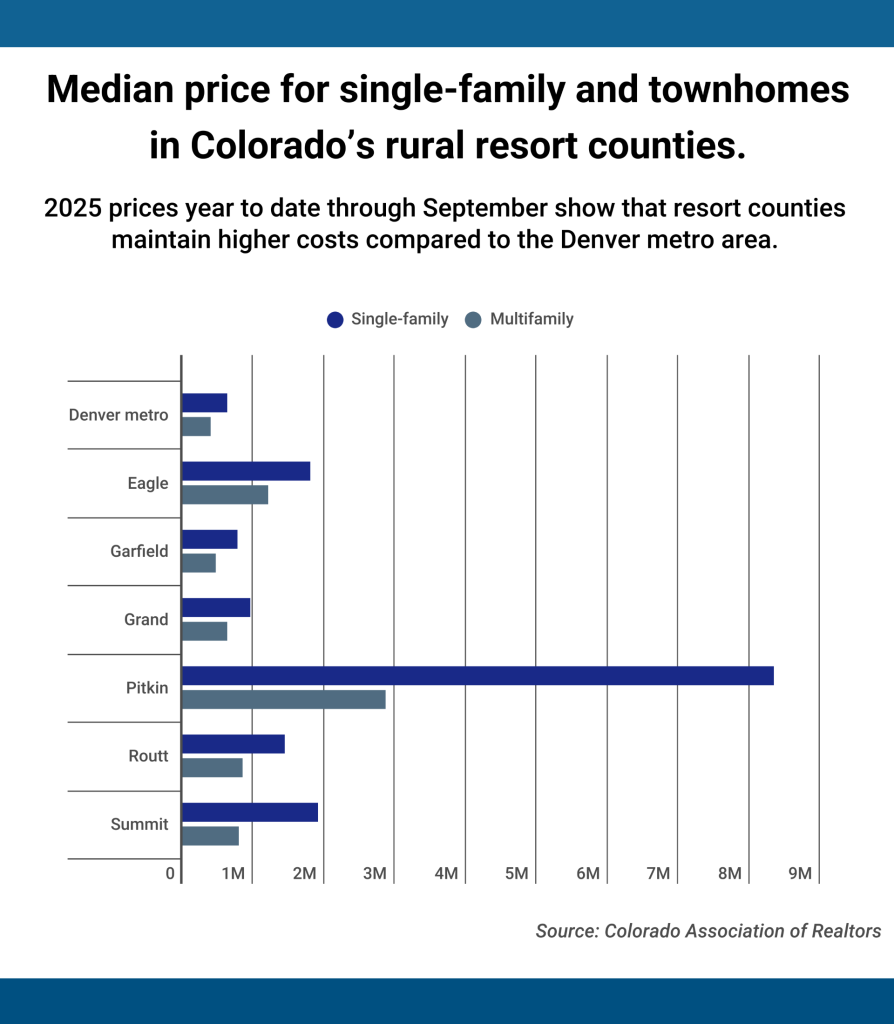

Housing advocates struggle at times to know where the right income cut-off is for their projects. That can put locals in a bind, like the Messers, who straddle the line of barely qualifying for affordable housing, yet make nowhere near enough to buy on the open market, where the median cost of even a condo is $1.2 million in their county.

Area median income limits have also, at times, led to affordable housing units sitting empty, either because the eligibility is too restrictive or because units are still too pricey. Because income data is used to set prices, it can translate to affordable housing that some say isn’t always affordable.

It’s a word housing advocates themselves have sometimes avoided, opting instead for terms like “workforce” or “community housing.”

“There’s always this push and pull,” said Kimball Crangle, Colorado Market President for Gorman & Company, an affordable housing developer that works across the High Country and Denver metro area. “Building the wrong type of supply doesn’t do anybody any good.”

Straddling the income limit

For the past seven years, Spencer and Camille Messer have called the Maloit Park mobile community in Minturn their home.

Owning their unit is the only reason they’ve been able to stay in the valley for that long, they said. But they’re preparing for the possibility that their time may be limited.

The Eagle County School District is currently considering redeveloping the land beneath the couple’s mobile home, which the district owns, and building around 130 affordable housing units, most of which would be for district staff.

That could include 64 for-sale homes built by Habitat for Humanity Vail Valley, though those plans are not yet finalized, and any redevelopment could still be years away. Residents would be notified a year out before any vertical construction is slated to begin, and all current occupants have been made aware of the potential plans, according to district spokesperson Matt Miano.

The Messers want peace of mind that their family won’t be displaced and have looked to Habitat as their solution. When they applied for a home last year, they were denied because they made roughly $26,000 over Habitat’s cutoff of 80% of the area median income, which, in 2024 figures, translated to $104,000 for a family of four.

They may still have another chance, though, if Habitat moves forward with building homes at the couple’s mobile home site. That’s because the nonprofit has an exception to its income limit when it comes to school district housing, allowing district employees who make up to 100% of the area median income to qualify for those units.

That, coupled with a shift in median income data this year, puts them just below the 100% median income cap, but only by about $3,000.

“It still feels like a strange spot to be in,” said Camille Messer, who wonders if she may need to drop her hours at Vail Health even more to ensure they don’t go outside the income threshold in future years.

The tradeoff could mean losing her seniority and benefits, like health insurance. The couple said they also need to be wary of other expenses, like child care for both their children, which costs around $1,600 a month. And just staying under Habitat’s income cap doesn’t mean they’re a shoo-in for a home. They’ll be competing with likely hundreds of other school district staff for a limited product.

“It’s a wild thing, too, thinking about my coworkers,” Spencer Messer said. “Over half of us have master’s degrees, so on paper it seems like we should be making so much money … and we’re still in this boat of also still struggling with housing.”

Elyse Howard, director of development for Habitat for Humanity Vail Valley, said area median income “often feels like a measurement that is kind of arbitrary,” adding that it doesn’t capture the true fiscal reality for many working families.

She said that’s why Colorado, and especially resort areas, need more housing supply aimed at a broader range of income types because the “need has gotten so much bigger.”

“At the end of the day, we can’t serve everybody in need of affordable home ownership, and so building out that housing continuum is really important,” Howard said.

Income data doesn’t always align with resort areas’ needs

Income limits present a conundrum for housing providers: They want to target a broader range of workers across the income spectrum, but funding for those projects is harder to come by.

What is available is often targeted at lower area median income brackets, like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, a bedrock federal program that can cover as much as 70% of an affordable housing project’s costs and is reserved exclusively for rental units.

Between 1987 — when the tax credits were first deployed — and 2023, it has helped create 3.7 million housing units across the U.S., according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The funding, however, is only for units that serve households making between 30% and 80% of the area median income. While those types of apartments can be found throughout the High Country, some mountain communities have struggled at times to fill them, with local leaders saying that the income bracket that would be needed is nearly unlivable for workers in resort towns.

In Aspen last month, housing officials worked to fill several vacancies at the 40-unit Aspen Country Inn, a Low-Income Housing Tax Credit project. The cutoff to qualify for those units is 50% of the area median income, which equates to $48,050 for an individual and $54,900 for a two-person household.

“In Pitkin County, there are very few jobs that make less than that,” said Matthew Gillen, executive director for the Aspen-Pitkin Housing Authority.

At $48,050 a year, for example, a local worker would be making just over $23 per hour. Gillen said that’s comparable to what fast food employees are paid in El Jebel, a small community 20 miles north of Aspen.

Still, fewer than 130 of the 1,500 housing units that the Aspen-Pitkin Housing Authority manages utilize the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and other housing projects serve well over 100% of the median income, according to Gillen.

But there also tend to be fewer subsidies for housing providers to tap into at that income level, without which it becomes harder to keep rates affordable. Local leaders worry that as area median income data changes year-to-year, it’s driving housing prices — particularly for rental units — that are still too burdensome for the workforce.

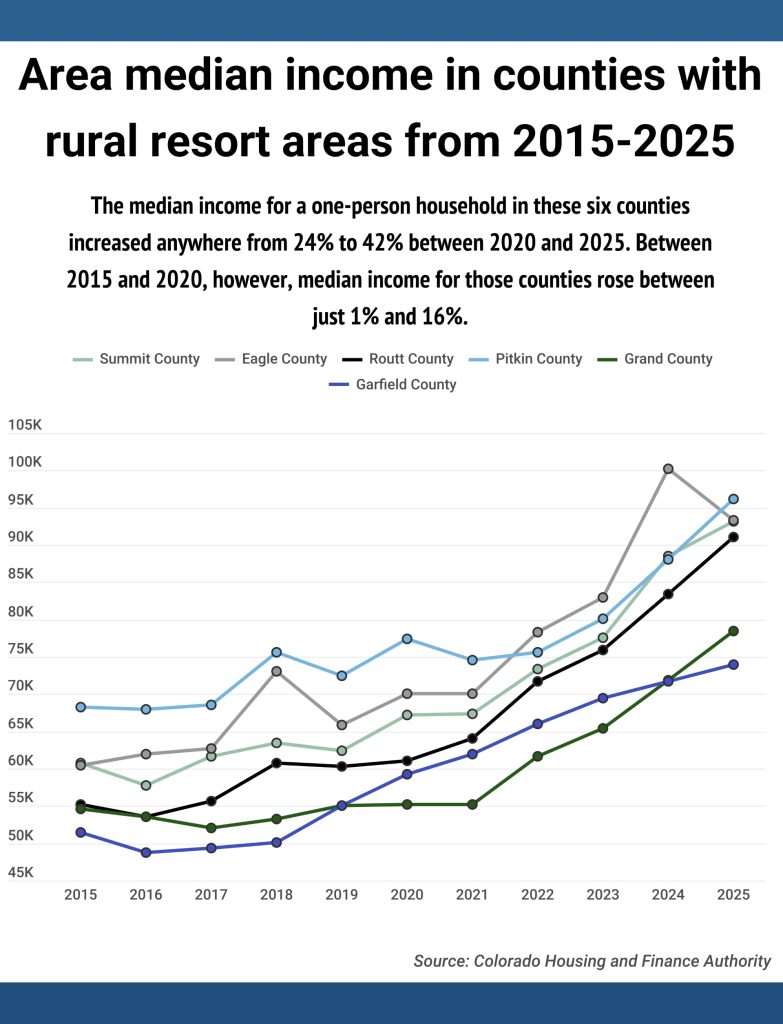

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, resort areas have seen erratic swings in their median income figures, which officials say is likely due to the migration of wealthier remote workers who flocked to mountain towns during the early years of the pandemic. Yet housing advocates aren’t seeing those income figures reflected in their workforce.

Routt County, home to Steamboat Springs, saw a nearly 50% jump in area median income from 2020 to 2025 compared to just an 11% increase from 2015 to 2020. Other rural resort areas have seen similar trends, with their median income increasing at a far faster rate post-COVID compared to before the pandemic.

Jason Peasley, executive director for the Yampa Valley Housing Authority, said that as area median income rises, it’s pushed up the maximum rent that the housing authority can charge for its workforce units, of which it’s built hundreds over the years.

Yet Peasley wagers most working residents who live in those units haven’t seen their paychecks go up 50%. Area median income data, Peasley said, “is not analogous to wage growth.”

To further subsidize rents, Peasley said the housing authority will need to lean more on local funding for projects, such as revenue from the 9% short-term rental tax that Steamboat voters approved in 2022.

Other communities have employed similar strategies, with local governments routinely asking voters to sign off on new tax increases to fund a growing list of needs, with affordable housing usually at the top.

Yet local officials are finding those dollars stretched thinner as they struggle with the harsh realities of building in their high-elevation environments. Higher construction and land costs, coupled with a short building window and small labor pool, quickly drive up the cost of delivering an affordable housing project at an “affordable” price.

“But we also don’t have the revenue, the tax revenue, that we would need to make them affordable,” said Pogue, the Summit County commissioner. “With new construction in particular, you are seeing rents that are just too high.”

‘Not all projects are going to serve everybody’

Gabby Blassou and her fiance, Josh Walker, pay upwards of $2,400 a month for their 700-square-foot, two-bedroom Breckenridge apartment, one of 172 workforce housing units built by developer Gorman & Co., roughly 3 miles from the town’s Main Street.

Blassou, who works as a bartender at a Breckenridge steakhouse, said the rent sometimes eats up more than a third of her income, the threshold for what the federal government considers to be a “cost-burdened” household.

It’s also slightly more than she paid at her last Breckenridge home, which she found on the open market and where she lived for five years. At her current place, she doesn’t know if she’ll stay longer than two.

“I don’t know how people are supposed to afford these units,” Blassou said.

When Gorman unveiled Vista Verde II, the second phase of its affordable housing apartment complex, in fall 2024, it faced criticism from some locals over its prices. The units, a mix of studios, one-, two-, and three-bedrooms, were targeted at those making between 80% and 120% of the area median income.

For a time, Gorman was unable to fill some of its higher-priced units, which exceeded $3,500 a month for a three-bedroom apartment, and eventually offered discounts and even waived work requirements for tenants to help fill the vacancies.

Crangle, the Gorman Colorado market president, said the challenge for affordable housing developers is the lack of public subsidies to drive down those rental rates.

When rates are based on area median income data, it also means rents can skew towards what higher earners can afford.

That was the case for Blassou and Walker, who were initially offered a rental price of close to $3,000 a month for a unit meant to serve those at 120% of the area median income. In 2024, the year the couple applied, that would’ve represented a dual income of $117,000.

In reality, their household earnings come almost entirely from Blassou’s bartending job, which pays around $60,000 a year. Walker is a full-time student in nursing school and occasionally works as a barista to help cover groceries or other expenses. The couple estimates he brings in around $10,000 a year.

Walker said his part-time income, coupled with his savings, was initially included in the couple’s area median income assessment, which is why they were offered a higher rent price. For him, it reflects the flaws in area median income data.

“There’s too many people who are well above the working class who are getting tossed into it,” Walker said.

While the couple was ultimately able to have their income reassessed and secure an apartment at a lower price, neither says they would call it “affordable.” Their unit is targeted to those making up to 80% of the area median income, which, for a two-person household, is $85,120 — around $15,000 more than Blassou and Walker make.

“It does raise concerns over whether or not this is a place that can provide longevity,” Walker said. “I’m not really sure how we’re supposed to move up the ladder.”

Laurie Best, the town of Breckenridge’s longtime housing director, said while Vista Verde II still serves a vital subset of the community, it also shows that there’s a need for lower rental rates for working residents. Most of the calls she got from residents who were interested in the project had to do with not being able to afford the price, she said.

Best said the town is currently reevaluating its affordable housing plan to better understand which residents are still being underserved.

“Not all projects are going to serve everybody, and that seems to be the biggest frustration,” Best said. “I would agree that we do have some more work to do in terms of trying to keep these lower-income households here. It’s challenging.”

Crangle said she worries that local governments who want these types of housing projects “don’t have public subsidies to satisfy the true gap,” adding that funding sources for affordable developments are “extremely scarce and limited.”

Vista Verde II, for example, was supported with roughly $8 million in loans from the town of Breckenridge, along with land that the town provided. Yet that funding only accounted for a fraction of the project’s total cost, which exceeded $80 million, most of which was funded through a construction mortgage.

“At the end of the day, I think we’re just in a time period where affordability is really challenging, housing is harder to build and rent to what locals can truly afford,” she said.

Pushing for more income flexibility

In downtown Glenwood Springs, Habitat for Humanity Roaring Fork Valley is testing a novel strategy for the nonprofit with its latest housing venture: no income limits on certain units.

At The Carter, an 88-unit apartment complex that Habitat purchased and converted into for-sale condos, the nonprofit is selling homes priced between 80% and 150% of the area median income. Some have no income cutoffs, though buyers are still required to work in the community.

For Habitat, it’s an acknowledgement of the growing need for more creative housing strategies.

“There’s so many boxes and requirements to fit perfectly within these other affordable housing programs in the valley,” said Darla Callaway, Habitat for Humanity Roaring Fork Valley’s chief executive officer.

“They’re good, they’re necessary, they’re important,” she continued, “but we recognized that we needed a more flexible tool to address some of the needs of those that are completely left out of these other programs.”

That’s the case for many families in the Roaring Fork Valley, where the current median price for a single-family home ranges from nearly $800,000 in Garfield County to over $8.3 million in Pitkin County, home to Aspen, Callway said.

Habitat’s Roaring Fork affiliate was able to offer income flexibility at The Carter thanks to partnerships with local governments and businesses that brought in funding for the project that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible. In exchange, those entities were given the “right” for one of their employees to purchase a unit.

While Callaway isn’t yet ready to say whether that will be a model for other Habitat groups to emulate, she feels like, so far, the strategy has been a success.

Local governments, too, are looking at ways to make income limits more malleable.

In Vail, housing officials are planning to use an “income priority” approach at their Southface project, formally referred to as West Middle Creek.

The project consists of 268 for-rent apartments, which the town is building on the north side of North Frontage Road. Those units will have prices targeted at 100% to 120% of the area median income, but officials will allow for a buffer for households that apply.

For example, someone making 130% of the median income could apply for a unit priced at 120%, and the town could increase eligibility even more, depending on demand.

Town of Vail Housing Director Jason Dietz said the strategy is meant to ensure that median income data isn’t used as the “ceiling” for what renters can afford, but instead serves as the “floor.”

Still, a lack of subsidies for higher-income projects means local governments take on more financial burden. Vail is using tax-exempt bonds to generate $189 million in upfront money for the Southface project, which could end up costing the town more than half a billion dollars over the next 40 years.

Dietz said the town also wouldn’t be able to make the project pencil without the higher income-based units.

“We ran scenarios where we tried to make it all 100% (area median income) rates,” Dietz said. “The numbers were far too big to make that project financially viable. We would have needed to bring in tens and tens of millions of dollars more cash.”

Can area median income be made to work better?

Housing advocates aren’t expecting that area median income, as a metric for affordable housing, is going away any time soon.

“Particularly for a tourist economy, it’s just going to be unreliable, but I also have not been able to find any alternatives that make more sense,” said Pogue, the Summit County commissioner.

That doesn’t mean that efforts aren’t underway to try and make it better.

Democratic U.S. Rep. Joe Neguse, whose congressional district includes Colorado’s central and northern mountain communities, has introduced legislation that would reform area median income calculations for resort areas.

Dubbed the Housing Fairness for Mountain Communities Act, the bill would allow counties to calculate their area median income based on ZIP code or region, rather than at the county level, which Neguse says could more accurately reflect mountain towns’ housing needs. The measure was introduced in 2023, but it has not yet advanced.

At the state level, most of Colorado’s affordable housing funding comes from Proposition 123, a tax measure approved by voters in 2022 that is projected to generate more than $300 million for housing initiatives every year in the form of loans and grants.

That funding is typically for for-sale housing aimed at 100% or below the area median income, or rental housing aimed at 60% or below. State lawmakers representing ski towns, however, successfully pushed for legislation in 2023 that allows rural resort communities to receive funding for projects that serve up to 140% of the area median income.

Of the first round of available funding from Proposition 123, which went out last year, $26.9 million was issued for development projects in rural and resort counties across the Western Slope. Combined, those funds will have helped create 685 workforce housing units.

State lawmakers in 2024 also approved a pilot program for middle-income housing tax credits aimed at projects that serve 80% to 120% of the area median income, though funding is limited. Lawmakers allocated $5 million for the program for 2025 and 2026, and $10 million annually for 2026 through 2029. The first round of that funding recently went out to a handful of projects, including a 70-unit affordable rental development in Fraser.

Still, if housing advocates “want to take advantage of some of the funding opportunities, then we have to live in that (area median income) world,” said Best, the Breckenridge housing director.

But they also aren’t willing to let perfection stifle progress.

Pogue said, despite the challenges, she has yet to see a Summit County housing project that wasn’t needed. She points to one of the county’s most recent developments, a 52-unit rental complex built in partnership with Breckenridge, that began leasing last year.

It received over 1,000 applications.

“Given the intense need that we see … I think it is essential that we continue to try,” Pogue said. “Ultimately, we have to continue to invest in housing and support our workforce.”