As Colorado mountain towns push for affordable housing, unreliable income data complicates their efforts

Area median income has long been the language of the housing world. Some housing advocates question whether it’s helping — or hindering — their affordability goals. I

Ben Roof/Special to the Vail Daily

Spencer and Camille Messer are worried about getting a raise.

The Eagle County couple, who live in a mobile home with their two children — aged 4 and 2 — may finally qualify for a highly coveted, deeply subsidized house through Habitat for Humanity, one of the few options for skirting the area’s sky-high real estate prices.

Looming development plans for their mobile home community may eventually force them to move. Neither wants to go back to renting, and they say a Habitat house may be their best — and only — option for staying in the Vail Valley.

But like most affordable housing in mountain towns, these homes are in short supply, high demand, and often come with strict income limits based on a longstanding, but imperfect, federal metric. If either of them sees even a small pay bump — any more than 2.5% — they may fall outside the cutoff to qualify.

“It’s the strangest type of housing insecurity,” said Spencer Messer, who works as an English teacher and cross-country coach at Battle Mountain High School. “It’s just weird when you have a career and you do as many things as you can to better yourself … that theoretically should put us in a better position to try to buy something.”

“We have to be cautious,” said Camille Messer, a part-time nurse at Vail Health, “about making sure that we’re not making too much money.”

As mountain communities race to dig themselves out of an affordable housing crisis, the range of housing needs is growing across a broader income spectrum.

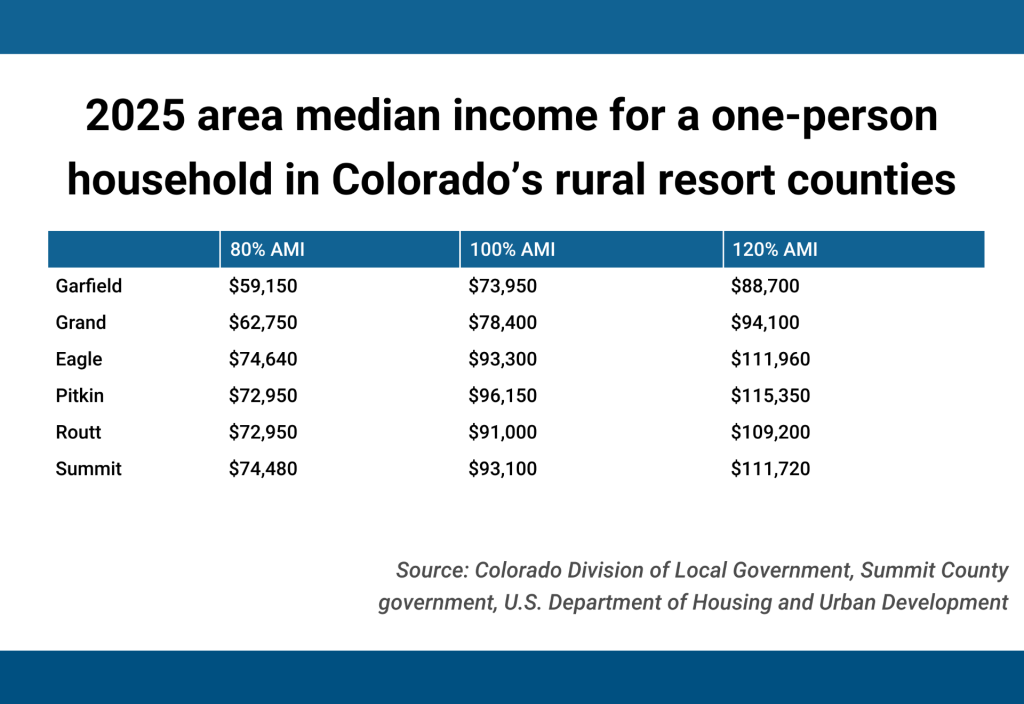

For housing providers, that often means looking at their county’s area median income, which is calculated each year by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and meant to represent the midpoint for earners in that community. That data is also typically used to set both price and eligibility for affordable housing projects.

But in Colorado’s High Country, local leaders say the data can be easily skewed.

“In a community like ours, where you have very, very high incomes and very, very low incomes, it’s not a reliable indicator of where the majority of the community actually is,” said Tamara Pogue, a Summit County commissioner who often works on housing policy.

Rural resort areas have smaller sample sizes and larger wealth disparities. Median income figures also include not just wages but investment earnings and retirement income, which can further tilt the numbers toward higher earners. And with much of the workforce in industries where they can make tips and overtime pay, and face slow and busy months, their income can often fluctuate throughout the year.

Housing advocates struggle at times to know where the right income cut-off is for their projects.

That can put locals in a bind, like the Messers, who straddle the line of barely qualifying for affordable housing, yet make nowhere near enough to buy on the open market, where the median cost of even a condo is over $1 million in their county.

Income limits have also, at times, made it difficult for housing providers to find people to fill units because of the strict cutoffs. And because income data is used to set prices, housing advocates worry it can translate to affordable housing that some say isn’t always affordable.

It’s a word housing advocates themselves have sometimes avoided, opting instead for terms like “workforce” or “community housing.”

“There’s always this push and pull,” said Kimball Crangle, Colorado Market President for Gorman & Company, an affordable housing developer that works across the High Country and Denver metro area. “Building the wrong type of supply doesn’t do anybody any good.”

Straddling the income limit

For the past seven years, Spencer and Camille Messer have called the Maloit Park mobile community in Minturn their home.

Owning their unit is the only reason they’ve been able to stay in the valley for that long, they said. But they’re preparing for the possibility that their time may be limited.

The Eagle County School District is currently considering redeveloping the land beneath the couple’s mobile home, which the district owns, and building around 130 affordable housing units, most of which would be for district staff.

That could include 64 for-sale homes built by Habitat for Humanity Vail Valley, though those plans are not yet finalized, and any redevelopment could still be years away. Residents would be notified a year out before any vertical construction is slated to begin, and all current occupants have been made aware of the potential plans, according to district spokesperson Matt Miano.

That could include 64 for-sale homes built by Habitat for Humanity Vail Valley, though those plans are not yet finalized, and any redevelopment could still be years away. Residents would be notified a year out before any vertical construction is slated to begin, and all current occupants have been made aware of the potential plans, according to district spokesperson Matt Miano.

The Messers want peace of mind that their family won’t be displaced and have looked to Habitat as their solution. When they applied for a home last year, they were denied because they made roughly $26,000 over Habitat’s cutoff of 80% of the area median income, which, in 2024 figures, translated to $104,000 for a family of four.

They may still have another chance, though, if Habitat moves forward with building homes at the couple’s mobile home site. That’s because the nonprofit has an exception to its income limit when it comes to school district housing, allowing district employees who make up to 100% of the area median income to qualify for those units.

That, coupled with a shift in median income data this year, puts them just below the 100% median income cap, but only by about $3,000.

“It still feels like a strange spot to be in,” said Camille Messer, who wonders if she may need to drop her hours at Vail Health even more to ensure they don’t go outside the income threshold in future years.

The tradeoff could mean losing her seniority and benefits, like health insurance. The couple said they also need to be wary of other expenses, like child care for both their children, which costs around $1,600 a month. And just staying under Habitat’s income cap doesn’t mean they’re a shoo-in for a home. They’ll be competing with likely hundreds of other school district staff for a limited product.

“It’s a wild thing, too, thinking about my coworkers,” Spencer Messer said. “Over half of us have master’s degrees, so on paper it seems like we should be making so much money … and we’re still in this boat of also still struggling with housing.”

Elyse Howard, director of development for Habitat for Humanity Vail Valley, said area median income “often feels like a measurement that is kind of arbitrary,” adding that it doesn’t capture the true fiscal reality for many working families.

She said that’s why Colorado, and especially resort areas, need more housing supply aimed at a broader range of income types because the “need has gotten so much bigger.”

“At the end of the day, we can’t serve everybody in need of affordable home ownership, and so building out that housing continuum is really important,” Howard said.

Income data doesn’t always align with resort areas’ needs

Income limits present a conundrum for housing providers: They want to target a broader range of workers across the income spectrum, but funding for those projects is harder to come by.

What is available is often targeted at lower area median income brackets, like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, a bedrock federal program that can cover as much as 70% of a project’s costs and is reserved exclusively for rental units.

Between 1987 — when the tax credits were first deployed — and 2023, it has helped create 3.7 million housing units across the U.S., according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The funding, however, is only for units that serve households making between 30% and 80% of the area median income. While those types of apartments can be found throughout the High Country, some mountain communities have struggled at times to fill them, with local leaders saying that the income bracket that would be needed is nearly unlivable for workers in resort towns.

In Aspen last month, housing officials worked to fill several vacancies at the 40-unit Aspen Country Inn, which received Low-Income Housing Tax Credit funding. The cutoff to qualify for those units is 50% of the area median income, which equates to $48,050 for an individual and $54,900 for a two-person household.

“In Pitkin County, there are very few jobs that make less than that,” said Matthew Gillen, executive director for the Aspen-Pitkin Housing Authority.

At $48,050 a year, for example, a local worker would be making just over $23 per hour. Gillen said that’s comparable to what fast food employees are paid in El Jebel, a small community 20 miles north of Aspen.

Still, fewer than 130 of the 1,500 housing units that the Aspen-Pitkin Housing Authority manages utilize the tax credits, and other housing projects serve well over 100% of the median income, according to Gillen.

But there also tend to be fewer subsidies for housing providers to tap into at that income level, without which it becomes harder to keep rates affordable. Local leaders worry that as area median income data changes year-to-year, it’s driving housing prices — particularly for rental units — that are still too burdensome for the workforce.

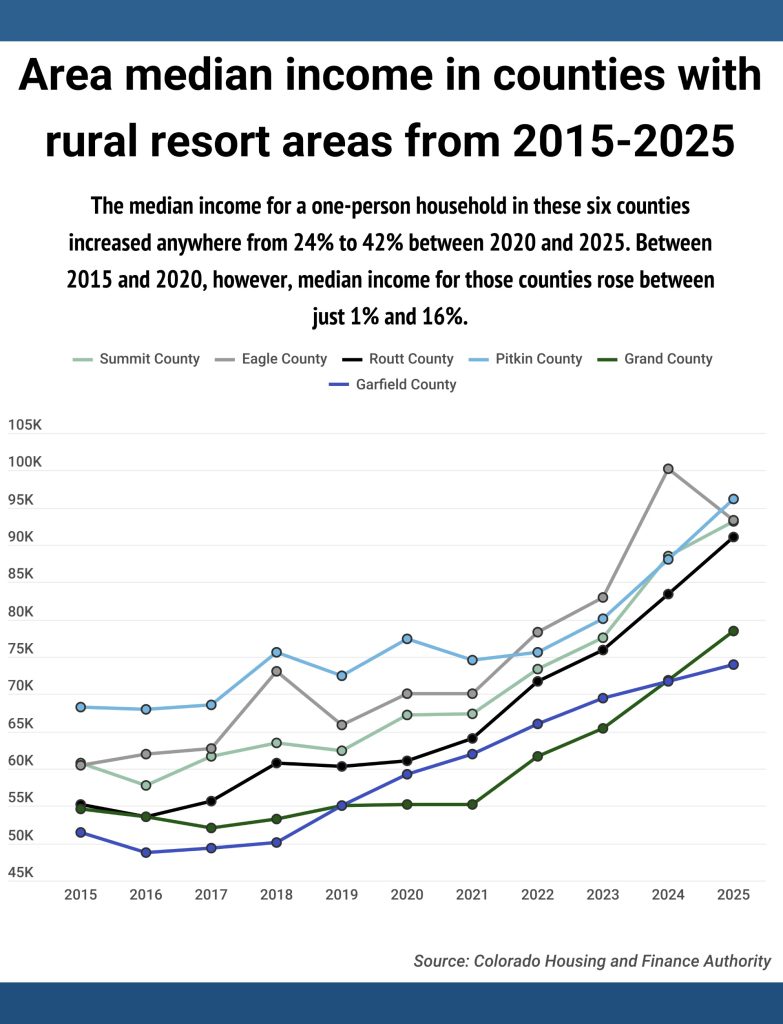

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, resort areas have seen erratic swings in their median income figures, which officials say is likely due to the migration of wealthier remote workers who flocked to mountain towns during the early years of the pandemic. Yet housing advocates aren’t seeing those income figures reflected in their workforce.

Routt County, home to Steamboat Springs, saw a nearly 50% jump in area median income from 2020 to 2025 compared to just an 11% increase from 2015 to 2020. Other rural resort areas have seen similar trends, with their median income increasing at a far faster rate post-COVID compared to before the pandemic.

Jason Peasley, executive director for the Yampa Valley Housing Authority, said that as area median income rises, it’s pushed up the maximum rent that the housing authority can charge for its workforce units, of which it’s built hundreds over the years.

Yet Peasley wagers most working residents who live in those units haven’t seen their paychecks go up 50%. Area median income data, Peasley said, “is not analogous to wage growth.”

To further subsidize rents, Peasley said the housing authority will need to lean more on local funding for projects, such as revenue from the 9% short-term rental tax that Steamboat voters approved in 2022.

Other communities have employed similar strategies, with local governments routinely asking voters to sign off on new tax increases to fund a growing list of needs, with affordable housing usually at the top.

Yet local officials are finding those dollars stretched thinner as they struggle with the harsh realities of building in their high-elevation environments. Higher construction and land costs, coupled with a short building window and small labor pool, quickly drive up the cost of delivering an affordable housing project at an “affordable” price.

“But we also don’t have the revenue, the tax revenue, that we would need to make them affordable,” said Pogue, the Summit County commissioner. “With new construction in particular, you are seeing rents that are just too high.”

As Colorado mountain towns push for affordable housing, unreliable income data complicates their efforts

As mountain communities race to dig themselves out of an affordable housing crisis, the range of housing needs is growing across a broader income spectrum.