Artistic structures that hold art

A look at four of Aspen’s cultural institutions

Special to The Aspen Times

Austin Colbert/The Aspen Times

Editor’s note: A version of this story appeared in Winter in Aspen and Snowmass 2025/26.

It’s only natural for structures that house art to look artistic themselves, and that’s certainly the case with these four buildings.

The Aspen Art Museum

The Aspen Art Museum, a free, non-collecting and purpose-built institution that works primarily with living artists, exudes a physicality that is vital to how artists experience it. Architect Shigeru Ban designed it to allow for works that respond directly to the building and its surroundings. Founded in 1979 by artists, that spirit continues to guide those involved.

The structure was designed as a porous, living museum, with indoor and outdoor elements that flow into one another. Precious Okoyomon’s rooftop garden, which evolved over two years in dialogue with Aspen’s climate and light, is an example of how the museum supports site-specific practice. The rooftop is one of the only places in Aspen where you can take in a full 360-degree view of the surroundings, and the cafe makes it a gathering place as much as a museum.

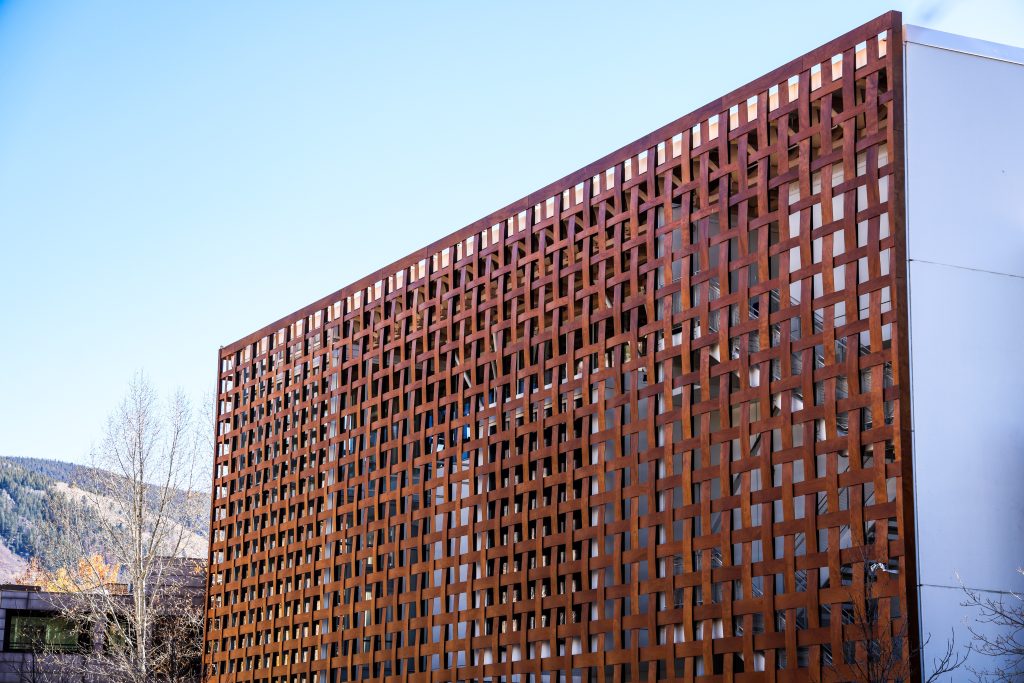

“With its wooden lattice, open-air rooftop, and expansive staircases, the museum creates a living environment where artists can test ideas and audiences can encounter them in ways that feel inseparable from Aspen,” says Nicola Lees, the museum’s artistic director and CEO.

The woven façade that wraps the building shifts with the light.

“People often remark on the wooden lattice, which has a physical presence that echoes the Aspen landscape,” she says. “The museum holds art, yet the building itself shapes perception and experience, inviting the public into dialogue with our exhibitions before they even step inside.”

Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies

The Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies is an international treasure. You feel the energy of the Aspen Idea when you walk into this building, which was designed so sensitively. It incorporates architecture that embodies the principles of the Bauhaus School of Design, of which Herbert Bayer was the last living member.

He based the building on fundamental geometries. It also embodies human’s understanding of, and connection to, nature. Patterns of nature and diagrams of the Aspen topography were critical to Bayer’s work. Using squares, octagons, and circles, Bayer’s artwork and architecture explored nature and what forms it inspires.

“When we first started designing on the campus, it was to respond to his architecture and artworks and to create a place for the public … to come and experience these forms that are inextricably connected to their site and to nature,” says Jeffrey Berkus, a design architect who spent considerable time with Bayer in his later years and worked on the designs of the buildings surrounding the Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies.

The center was built as a cradle to hold Bayer’s artworks, to facilitate finding common ground, and to educate future generations about why and how important Bayer’s work are.

“It’s designed as a pavilion and temple within which you are honoring that which is sacred about humanity and to emphasize the positive pieces we have culturally,” Berkus says.

The building itself is a series of squares and golden sections whose circulation patterns respected the exhibition spaces that Bayer had designed over time. It was designed as a square that paid honor to the Boetcher Center, which Bayer designed as his last building on the Aspen Institute. The two buildings share a common courtyard and are linked by a curved path: the Golden Section. There’s a fluid curvilinearity in the way you move through the building. There are two ways in and out of every room and two sets of stairs, flowing down and up through the galleries, which is a parallel fluidity that you’ll see in Bayer’s canvases and buildings.

“Through your experience of the building, you are constantly connected through the window composition to the natural world,” Berkus says. “And it works.”

On the equinox in both March and September, the rising sun over Smuggler Mountain streams in straight through the front windows and down through the building.

Aspen Film Isis Theatre

There are probably a dozen Isis Theatres around the country. However, the Aspen Film Isis Theatre is a work of art unlike any others.

Kitty and Dominic Linza bought the Isis Theatre in 1968 and ran it for 30 years. Dominic used to say, “If you want to bring in a steak dinner, bring it in. You’re here to watch the movies.”

“That was the good ol’ days in the ’70s and ’80s,” says Charles Cunnifee, the original architect of the Isis Theatre. Instead of it falling into the hands of developers, he and a group of friends joined together and bought it from them. “The town once had two theaters. It was really important for us to save this theater, as it was the last chance for a movie theater in Aspen.”

The building as it stood had limited structural integrity, making it no easy feat to redevelop it to accommodate five screens instead of one. They renovated it completely, only keeping the historic front façade. They dug out 35 feet to create three stadium-style theaters below and two on the ground level and added a free-market penthouse. They also built affordable housing apartments above the building. Finally, the atmosphere, lighting, and acoustics all received a modern makeover.

“We worked with some Hollywood people on the sound system to get that right,” he says. “All the things that a modern cinema requires — we made the building work even better than it did before.”

The theme of the theater was and is the Egyptian goddess, Isis. Architectural elements project the nostalgia of the past. The lobby even features a statue of the goddess.

“When we did the renovation then, we really played up the Egyptian theme,” he says, adding that many Egyptian symbols and sculptures were incorporated in the stairwell, ceiling, and wallpaper. “Even the carpet — we had custom carpet made that had Egyptian symbols in it.”

The proprietors plan to always maintain the name, Isis, while also making it a vibrant gathering space for all ages — not only for film, but also for the community and for nonprofits.

Wheeler Opera House

From its 19th-century design to its carefully restored façade, the Wheeler hosts everything from world-class musicians to local improv troupes.

“It’s a space where architecture and artistry meet and where the venue becomes part of the performance,” says Nicole Levesque, marketing director for the Wheeler Opera House.

The building’s acoustics, sightlines, and ambiance all contribute to a memorable experience for both artists and audiences.

The sandstone façade is often the first thing people notice when they approach the building. Masonry work, tuckpointing, and local Peachblow sandstone from the Frying Pan Valley also stand out as distinctive features. The building’s unique blend of Italianate and Romanesque Revival styles — with arched windows, ornate detailing, and robust masonry — imbue a timeless character. Recent restoration efforts have brought these architectural features back to life, including historically accurate paint colors and the reversal of non-original alterations, ensuring the Wheeler remains both safe and historically authentic.

Once you walk through the doors, you’re immersed in a space that is both historically elegant and functionally modern.

“The Italianate and Romanesque Revival styles create a sense of grandeur and intimacy, which enhance everything from a solo acoustic set to a full theatrical production,” she says.

Built in 1889 and financed by Jerome B. Wheeler, it was once the third-largest opera house in Colorado. Wheeler wanted to give Aspen a cultural anchor, and architect W.J. Edbrooke’s design — both elegant and permanent — reflect Aspen’s aspirations as a mining town with cultural ambition. In the 1940s to ’60s, Herbert Bayer’s renovations introduced a minimalist aesthetic with Japanese lanterns, exposed beams, and later, a fusion of Victorian and Bauhaus elements. The Wheeler has stood the test of time as a gathering place — surviving fires, economic shifts, and evolving artistic trends. It is designated as a local landmark and included on the National Register of Historic Places.

“The Wheeler’s architectural style, materials, and scale were all chosen to give the community a sense of identity and pride. Inside, the intimacy of the space, the acoustics, and the historic charm are frequently praised by performers and audiences alike, and there’s a sense of warmth and authenticity that’s hard to replicate,” she says.

Today, it continues to serve as a hub for performance, conversation, and community — a living legacy.

Aspen One confirms skier death on Aspen Mountain

A skier died on Aspen Mountain Friday following a collision with a tree, according to a statement released by Aspen One’s communications team.